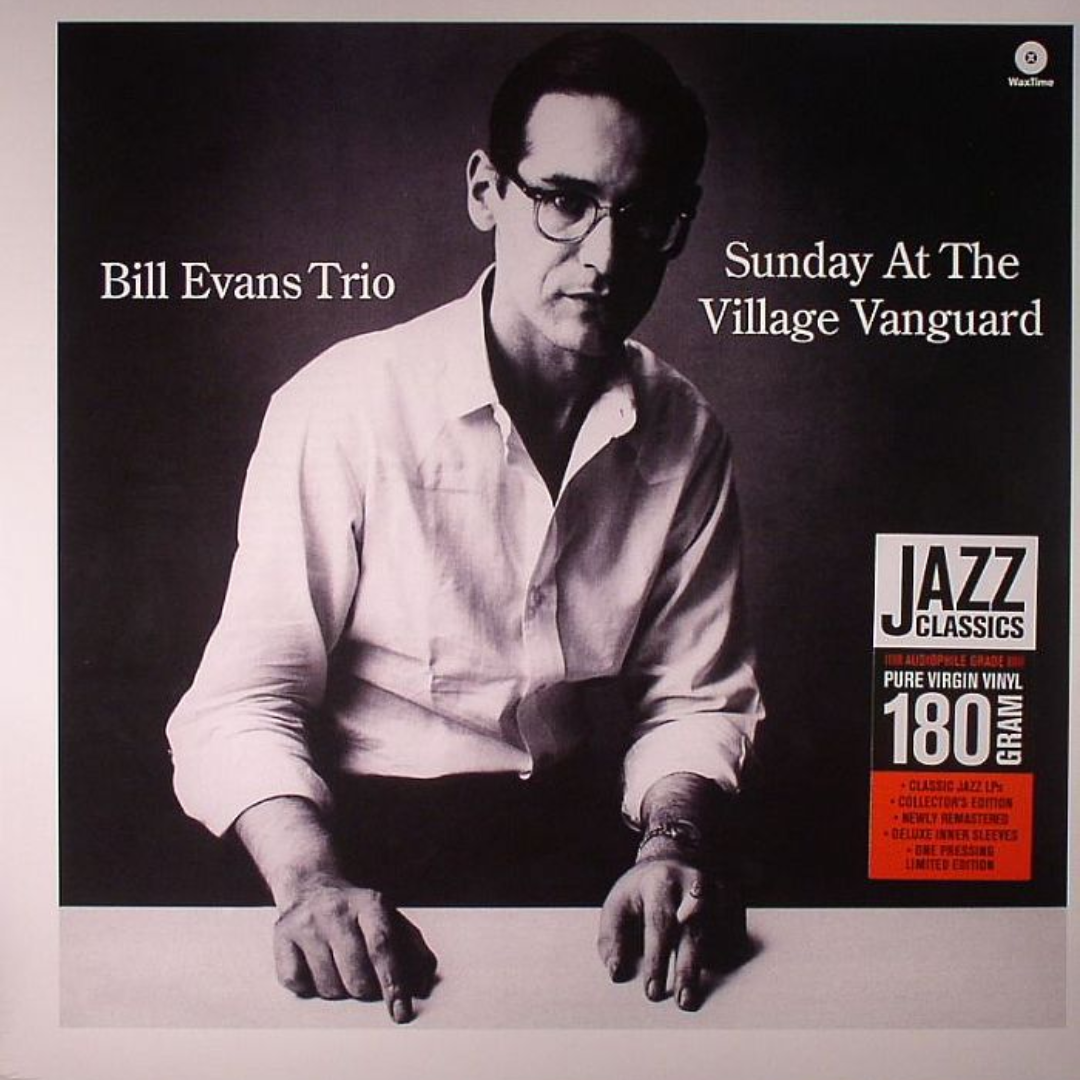

Bill Evans Trio’s – Sunday at the Village Vanguard (1961)

Bill Evans Trio’s – Sunday at the Village Vanguard (1961)

Out of stock — future drops announced to members of The Guide

The clinking of glasses, the soft murmur of conversation, the faint rustle of waiters moving between tables. Before a single note is played, you can already hear the space. The Village Vanguard, New York’s subterranean temple of jazz, has always had that presence: intimate, lived-in, resonant. On June 25, 1961, Bill Evans and his trio sat down in that room for a Sunday engagement. By night’s end, they had created one of the most intimate and enduring documents in jazz. Sunday at the Village Vanguard is more than a live album. It is the sound of a room, a band, and an idea of listening captured in fragile permanence.

The trio was Bill Evans on piano, Scott LaFaro on bass, and Paul Motian on drums. Their collaboration had been brief but incandescent. Evans, fresh from his transformative work with Miles Davis on Kind of Blue, had found in LaFaro a bassist of unprecedented lyrical freedom, and in Motian a drummer whose sensitivity was as important as his pulse. Together they reimagined the piano trio not as soloist with accompaniment, but as three equal voices engaged in conversation.

That Sunday was LaFaro’s last performance. Ten days later he was killed in a car accident at the age of twenty-five. This lends the record an added poignancy, but even without hindsight, the music feels charged with a rare intensity. There is no sense of routine here. Each tune unfolds with the risk and trust of genuine dialogue.

From the opening notes of “Gloria’s Step,” you can hear LaFaro’s independence. His bass is not tethered to Evans’s left hand; it is a voice of its own, melodic, unpredictable, agile. Evans responds with harmonic subtlety, Motian with brushes and cymbals that sketch rather than dictate time. The music is conversational in the truest sense: overlapping phrases, moments of silence, shifts in direction. You are listening not to a performance but to three people thinking aloud together.

“My Man’s Gone Now” becomes almost spectral in their hands. Evans’s chords hang in the air like unanswered questions, while LaFaro weaves lines of aching lyricism. Motian is sparse, often silent, intervening with a single brush stroke as though to underline a phrase. The silences matter as much as the notes. You can hear the audience leaning in, the room itself holding its breath.

There are standards here — “Alice in Wonderland,” “My Foolish Heart” — but they do not feel like repertoire so much as occasions for exploration. Evans never imposed virtuosity; his genius was in restraint, in the ability to say much with little. His voicings are like colours more than chords, shifting light rather than harmonic statements. LaFaro responds with restless energy, constantly pushing against expectation. Motian, ever elusive, avoids timekeeping in favour of atmosphere. The result is music that feels alive, unrepeatable, ephemeral.

The album’s production is crucial to its magic. Producer Orrin Keepnews resisted the temptation to clean the tapes too much. The clatter of cutlery, the occasional cough, the shuffle of feet — all remain. Far from distraction, they ground the music in place, reminding us this was not a studio construction but an event, fragile and contingent. The room becomes part of the record, its acoustics folding into the trio’s sound. This is why the album feels so immediate even decades later. It is not merely documentation; it is presence.

LaFaro’s contributions are the record’s beating heart. His solos are not interruptions but extensions of the conversation. His tone is light yet firm, his phrasing more like a horn than a traditional bass. On “Jade Visions,” his own composition, he leads the trio into an otherworldly space — haunting, weightless, suspended. The piece lasts less than four minutes, but it lingers like a dream. Listening today, knowing what would follow, the effect is devastating.

Evans himself often spoke of striving for “simultaneous improvisation,” a collective unfolding rather than spotlight solos. Sunday at the Village Vanguard is the clearest realisation of that aim. You can hear the trio listening as intently as they play, each phrase a response to what has just happened, each silence an opening for possibility. It is a form of empathy made audible.

Culturally, the album has become a touchstone. Countless piano trios cite it as influence, but few have matched its balance of fragility and strength. It is not virtuosic in the conventional sense; it is not about speed, volume, or display. Its mastery lies in understatement, in the ability to draw listeners into a world where nuance is everything. It proved that smallness could be vast, that intimacy could carry as much weight as grandeur.

To play it today is to feel time slow. The room you are in begins to resemble that Greenwich Village basement: close, dim, attentive. The music does not impose mood; it creates a space in which mood can emerge. The details — the ring of Evans’s pedal, the scrape of LaFaro’s fingers, the breath between Motian’s brush strokes — remind you that music is not only notes but gesture, texture, presence.

More than sixty years on, Sunday at the Village Vanguard has lost none of its intimacy. If anything, it grows more affecting with age, a reminder of what is possible when musicians trust each other completely. It is not an album of grand statements. It is an album of moments, strung together in fragile continuity, like a conversation you don’t want to end.

Couldn't load pickup availability