Alice Coltrane – Journey in Satchidananda (1971)

By Rafi Mercer

A harp glissando shimmers like sunlight on water. Then a drone begins, low and steady, grounding the space. Over it, a soprano saxophone enters — Pharoah Sanders, lyrical yet searching — and suddenly the room feels transformed. You are no longer in a club or a living room. You are in a temple, a sanctuary, a threshold between worlds. This is Alice Coltrane’s Journey in Satchidananda, released in 1971, one of the most transcendent records in the history of jazz.

Coltrane was at a crossroads when she made this album. Her husband, John Coltrane, had died in 1967, leaving her not only with grief but with the challenge of carrying forward a musical and spiritual legacy. She had already begun exploring her own path on Ptah, the El Daoud and A Monastic Trio, but Journey in Satchidananda crystallised her vision. It was not simply jazz. It was devotional music, rooted in the search for transcendence.

The title references her guru, Swami Satchidananda, whose teachings emphasised truth (sat), consciousness (chit), and bliss (ananda). The album is infused with that philosophy. It is music of presence, of meditation, of spiritual journeying. Yet it is not abstract. It is deeply physical, grounded in rhythm and resonance.

The opening track, “Journey in Satchidananda,” sets the tone. Coltrane’s harp creates a flowing, liquid texture, while Charlie Haden’s bass anchors the groove. Rashied Ali’s percussion, combined with Indian tabla from Tulsi and tamboura drone, creates a sound both rooted and otherworldly. Sanders’ saxophone soars above, not as virtuoso display but as prayer. The piece is hypnotic, cyclical, endlessly unfolding.

“Shiva-Loka” follows, with Coltrane’s piano entering more forcefully, chords resonant and deliberate. The percussion is intricate, the rhythm insistent, yet the overall effect remains meditative. “Stopover Bombay” is shorter but equally entrancing, its repetition evoking the sense of travel, of pause on a longer journey.

“Something About John Coltrane” is both tribute and invocation. Built around a drone, it allows space for reflection, for mourning, for continuity. “Isis and Osiris,” the closing track, stretches to eleven minutes, layering modal improvisation with deep, pulsing rhythm. The effect is ritualistic, as if calling forth ancient deities through sound.

What makes Journey in Satchidananda extraordinary is its fusion of traditions. Jazz improvisation meets Indian classical modes, Western instruments meet Eastern, spiritual longing meets grounded rhythm. Yet it never feels forced or eclectic. Coltrane integrates these elements with sincerity, humility, and clarity. The result is seamless: a sound world entirely her own.

The cultural significance of the album is vast. It became a cornerstone of what came to be called “spiritual jazz,” alongside works by Sanders, Sun Ra, and John Coltrane’s late recordings. But Alice’s voice was distinct. Where John’s music often reached for the ecstatic, hers leaned toward the meditative. Where his sound was fire, hers was water. Both sought transcendence, but by different paths.

Listening today, the album feels profoundly inclusive. Its invitation is gentle, its spirit welcoming. It does not demand technical knowledge of jazz or Indian music. It does not require the listener to believe in any particular faith. It asks only presence. Women and men, young and old, seasoned listeners or newcomers — all can step into its sound. That openness is part of its power.

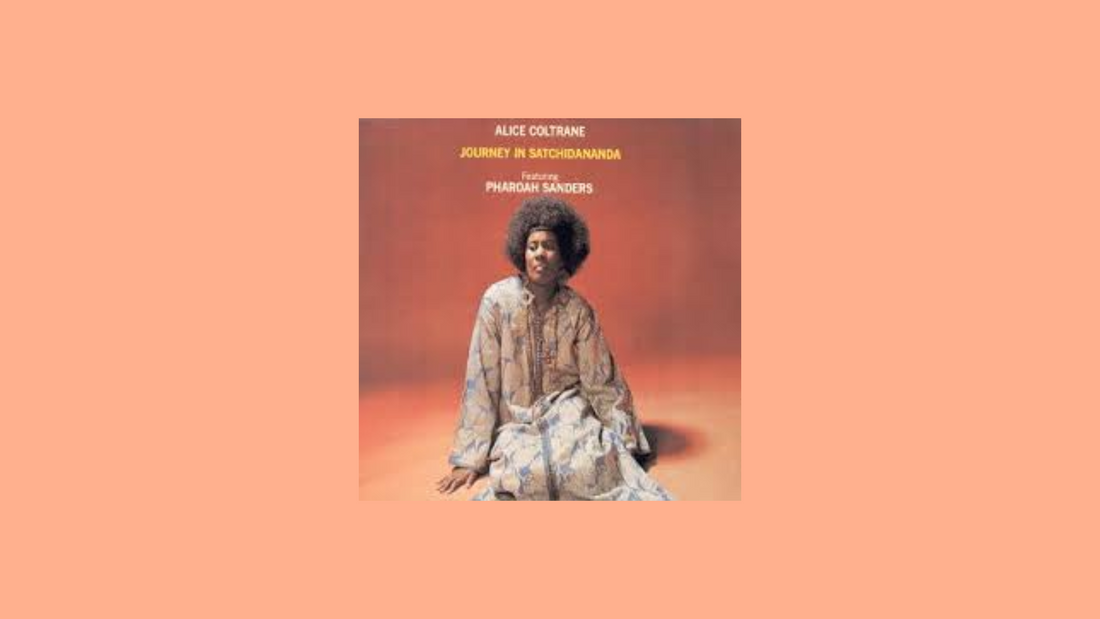

On vinyl, the resonance is physical. The bass hums through the body, the harp sparkles in the air, the drone fills the room with vibration. The slight surface noise only adds to the sense of ceremony, as if the record itself were alive, breathing with the listener. The artwork — Coltrane serene, seated in saffron robes — reinforces the essence: music not as performance but as devotion.

More than fifty years on, Journey in Satchidananda has lost none of its potency. If anything, in a culture of acceleration and distraction, its patience feels even more radical. It models a different way of being: attentive, meditative, present. It reminds us that listening is not only entertainment but practice, ritual, even prayer.

To play this record today is to step into Coltrane’s vision — a vision of music as path, as offering, as journey. The harp shimmers, the saxophone cries, the bass grounds, the drone sustains. And in the interplay of those elements, you are carried — not away, but deeper in.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.