Haruomi Hosono – Cochin Moon (1978)

By Rafi Mercer

There are albums that document a place, and there are albums that invent one. Haruomi Hosono’s Cochin Moon belongs firmly in the latter category. Released in 1978, it is a work of synthetic exotica — a shimmering, playful, and at times surreal soundscape inspired by Hosono’s travels in India, but filtered entirely through electronics. What emerges is not ethnography but dream: a fantasy India rendered in oscillators, sequencers, and bright, pulsing tones.

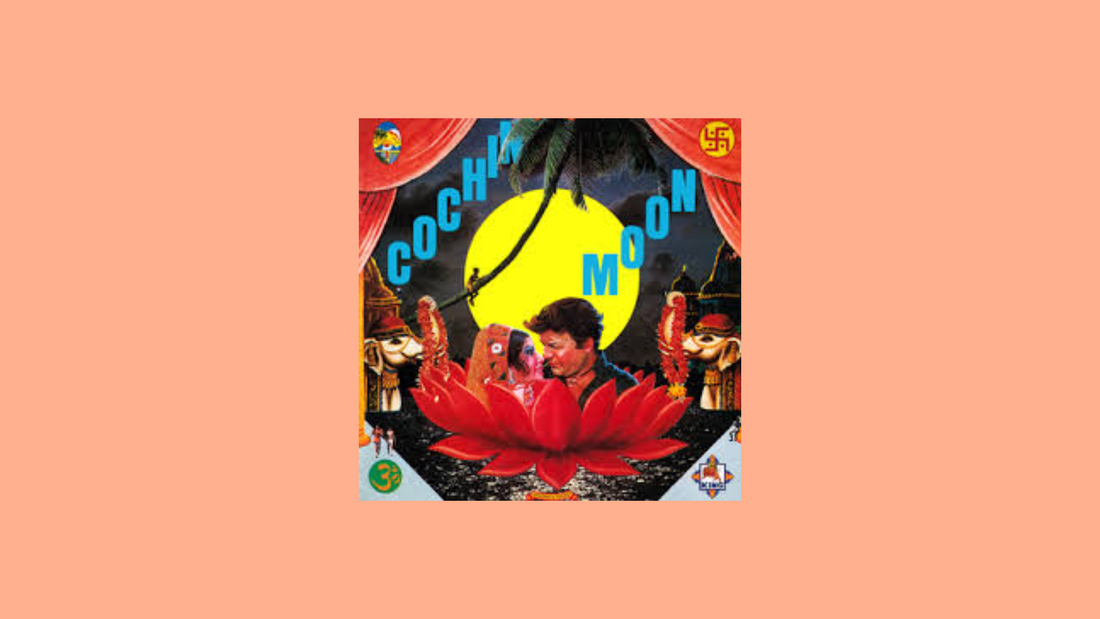

Hosono was already one of the most restlessly inventive figures in Japanese music. From his early work with the psychedelic band Happy End to the folk-rock textures of Hosono House, he had shown a taste for reinvention. Cochin Moon marked another turn. Fascinated by electronic music and the possibilities of the synthesiser, he set out to create an album that would evoke both travelogue and hallucination. To do so he enlisted artist Tadanori Yokoo, who provided the vivid, kaleidoscopic artwork, and co-producer Shigeru Suzuki. Together they created a record that feels as visual as it does sonic.

The album opens with “Hotel Malabar Upper Floor…Moving Triangle.” Already the intent is clear: bright synthetic tones dance across stereo space, layered over a pulsing rhythm that suggests movement, travel, disorientation. The sound is both playful and uncanny, like a neon-lit carnival seen through a heat haze. There are melodic fragments that hint at Indian scales, but they are refracted through electronics, transformed into something futuristic. Hosono is not imitating; he is inventing.

As the suite continues — for Cochin Moon is best heard as one continuous journey — the textures shift. “Hotel Malabar Ground Floor…Triangle Circuit on the Sea-Forest” deepens the rhythm, layering percussive blips that suggest both tabla and circuitry. “Hotel Malabar Inner Garden” slows into more meditative tones, synthetic birdsong flickering around drifting chords. Later movements grow denser, more chaotic, evoking bustling markets, psychedelic nights, strange machinery humming in some distant temple. The album closes with “Madam Consul General of Madras,” a piece as whimsical as its title, filled with synthetic fanfares and cartoonish effects.

What makes Cochin Moon remarkable is its balance of humour and craft. It is not parody, though it flirts with kitsch. It is not solemn, though it is carefully made. Hosono understood that electronic sound could be both playful and serious, capable of building entire imaginary worlds. The album delights in its artificiality. It does not attempt to disguise its synthetic nature; it revels in it. The “India” it conjures is not real but fantastical, a projection of travel fever and imagination.

At the time, Japanese electronic music was still an emerging field. Kraftwerk had already laid foundations in Europe, but Hosono’s approach was different. Where Kraftwerk imagined trains and motorways, Hosono imagined hotels, bazaars, and neon temples. His was a world of colour and sensuality, not industrial precision. In this sense, Cochin Moon feels closer to surrealism than to minimalism. It paints in bright hues, it laughs, it surprises.

Listening today, the album feels oddly prophetic. Its use of sequencers and synthetic percussion prefigures much of the electronic pop that Hosono would soon explore with Yellow Magic Orchestra, the group he co-founded later in 1978. You can hear the seeds of YMO’s playful futurism in these tracks — the gleeful embrace of artificial sound, the mixing of cultural references, the sense of technology as toy and tool alike.

On vinyl, the record’s warmth offsets its digital brightness. The crackle of playback grounds the otherwise weightless tones, making the fantasy feel tactile. The artwork too matters: Yokoo’s psychedelic collage of elephants, tigers, temples, and machinery situates the record as much in visual culture as in sound. Cochin Moon is an album to hold as well as hear, a Gesamtkunstwerk of image and sound.

The cultural afterlife of the record has been fascinating. Once a curiosity, it has since been embraced by collectors and ambient explorers as a classic of Japanese electronic music. Its humour, once mistaken for frivolity, is now recognised as part of its genius. By refusing solemnity, Hosono opened a different path for electronic sound: one where fantasy and play could be as vital as rigour.

To listen now is to step into a parallel world. It is not India, not Japan, not the future, not the past. It is all of them, folded into a sonic dream. The tones bubble and flash, the rhythms pulse and stutter, the melodies dissolve into colour. It is travel without destination, a hallucination pressed to vinyl.

Hosono would go on to many other things — from electronic pop to environmental sound design — but Cochin Moon remains singular. It is a reminder that imagination itself is a place, that music can invent geographies, that travel can be inward as much as outward. Play it, and you are not transported to Cochin, but to a dream of Cochin: stranger, brighter, freer.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.