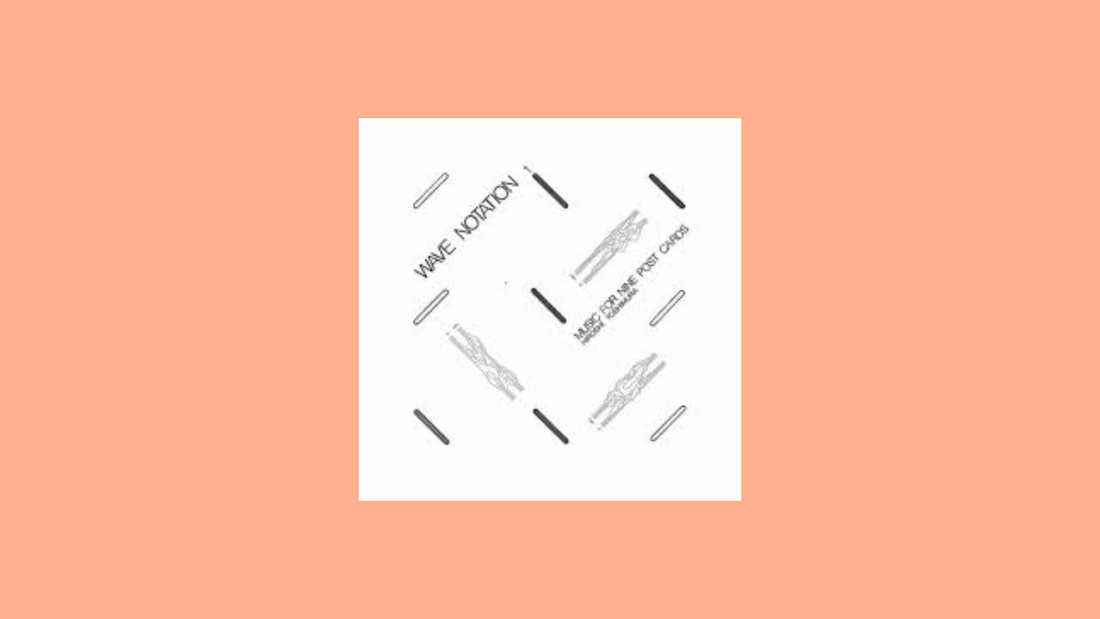

Hiroshi Yoshimura – Music for Nine Postcards (1982)

By Rafi Mercer

Imagine walking through a museum late in the day, the light falling soft across glass walls, the rooms nearly empty. Outside, clouds drift slowly; inside, your footsteps echo faintly. This is the atmosphere Hiroshi Yoshimura captures in Music for Nine Postcards, his 1982 debut — a record that seems to breathe with the spaces around it. It is not music that tells a story. It is music that notices: weather shifting, a shadow across a floor, time passing gently.

Yoshimura was not a household name in his lifetime. He worked quietly in Japan, composing for galleries, public spaces, installations. His intent was not to dominate but to accompany, to offer sound that enriched the environment without overwhelming it. In many ways he was part of a lineage of Japanese artists — designers, architects, gardeners — who understood that beauty often lies in restraint, in allowing space to remain space. Music for Nine Postcards is his clearest statement of that philosophy.

The album was originally conceived for the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo. Visitors moving through its glass and steel corridors would hear these pieces floating in the background. Each track is named simply: Water Copy, Clouds, Urban Snow, View from My Window. They are less compositions than sketches, each capturing a mood as fragile as the light at a certain hour.

The instrumentation is minimal: just piano and synthesiser, played with unhurried simplicity. Notes fall slowly, often in pairs, leaving long silences between them. The sustain pedal holds them into resonance, the synth adding faint colour, like mist around a lamp. Nothing develops in the traditional sense; instead, patterns recur, dissolve, return. It is music not of movement but of dwelling.

“Water Copy,” the opening track, sets the tone. Notes ripple in repetition, as if mirroring water disturbed by a breeze. “Clouds” floats with chords that barely shift, suspended in air. “Urban Snow” captures the hush of a city muted by weather — not grand storm, but a quiet snowfall that turns noise into softness. Listening, you feel your own pace slowing. Even the act of breathing seems to align with the rhythm, or rather the un-rhythm, of the record.

There is nothing exclusionary here, nothing coded for insiders. This is music anyone can step into. It does not ask for knowledge of jazz or ambient traditions. It does not demand recognition of virtuosity. Its beauty lies in its humility, in its willingness to be small. And yet, precisely because of that humility, it opens vast emotional territory. Women and men alike, seasoned listeners or curious newcomers, can find in it the same invitation: pause, look out the window, notice the world.

The warmth of Yoshimura’s presence is audible. Though the record is spare, it never feels cold. There is a friendliness to the phrasing, a sense of welcome. It is not the kind of minimalism that shuts you out; it is the kind that opens a door quietly and says: “Come in, sit, listen for a while.” In that way, it is an antidote to the often masculine-coded language of collecting, connoisseurship, or “serious listening.” Nine Postcards asks you only to be present.

For decades the album remained obscure, circulated among collectors, until its reissue in the 2010s. The rediscovery was met with near-universal wonder. Listeners spoke of how modern it sounded, how it seemed perfectly tuned to contemporary needs: music not of urgency but of patience, not of spectacle but of attention. It has since become a cornerstone of the Japanese ambient tradition, often grouped with Midori Takada’s Through the Looking Glass or Satoshi Ashikawa’s Still Way.

On vinyl, its fragility is heightened. The surface noise of the pressing blends with the music, as if part of the composition itself. The faint crackle becomes snowfall, or the hum of distant traffic, or simply another reminder of presence. This is not music for digital clarity; it is music for lived sound, sound that accepts imperfection.

Listening to it today, you realise how radical Yoshimura’s proposition remains. In a culture of speed, he offers slowness. In a world of endless assertion, he offers understatement. In a landscape of noise, he offers near-silence. And in that offering, he creates something more powerful than grand gestures: a space where listening becomes life itself.

Music for Nine Postcards is an album to live with. Put it on while reading, while watching rain at the window, while cooking, while sitting with someone you love. It does not compete. It accompanies, gently. And in doing so, it dignifies those ordinary moments, reminding us that they are never ordinary at all.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.