Mulatu Astatke – Ethiopian Jazz Volume 4 (1974)

By Rafi Mercer

A vibraphone glimmers, its notes hanging in the air like lanterns at dusk. Beneath it, a rhythm section locks into a steady, hypnotic pulse: bass low and round, drums clipped and precise, congas whispering at the edges. A horn enters, carrying a melody that sounds both familiar and utterly new — pentatonic yet modal, African yet modernist, mournful yet swinging. This is the sound of Mulatu Astatke’s Ethiopian Jazz Volume 4, released in 1974, the album that defined Ethio-jazz and placed Addis Ababa on the global musical map.

Astatke, born in 1943, was trained in London, New York, and Boston, studying classical, jazz, and Latin traditions before returning to Ethiopia. What he brought back was a hybrid form: Ethiopian melodic modes (known as qenet) fused with jazz improvisation, Afro-Latin rhythm, and funk grooves. Ethio-jazz was born. Volume 4 is the genre’s most iconic document, a record that captures the smoky nights of Addis clubs in the 1970s while pointing to a future where music could be both rooted and borderless.

The album’s opener, “Yèkèrmo Sèw,” is perhaps its most famous piece. A descending horn riff, hypnotic and melancholic, floats over a slow, heavy groove. The melody feels ancient, yet the arrangement is modern, anchored by Astatke’s vibraphone and electric organ. It is meditative and propulsive at once — a perfect example of Ethio-jazz’s balance of stillness and motion.

“Metche Dershe” brings more energy, horns stabbing with funk intensity over a brisk rhythm. “Gubèlyé” slows the pace again, its mournful horn lines stretching into blue territory. “Asmarina” has a lilting, almost Latin quality, evidence of Astatke’s years in New York absorbing salsa and Cuban jazz. Each track balances Ethiopian modal scales with the improvisatory spirit of jazz and the polyrhythms of Africa.

What makes Ethiopian Jazz Volume 4 so extraordinary is its atmosphere. The arrangements are sparse yet evocative, the grooves deep but unhurried. The horns carry melodies that seem to speak across centuries, while the vibraphone adds a shimmering, modern texture. It is music that feels both local and universal, rooted in Addis but resonant everywhere. You can hear it in dimly lit clubs, in city streets, in solitary listening rooms. It is worldly and intimate at once.

The cultural context is vital. Ethiopia in the early 1970s was on the cusp of upheaval, the monarchy soon to fall and the Derg military regime to take power. Addis was a cosmopolitan city, its nightlife vibrant, its musicians experimenting. Astatke’s music embodied that cosmopolitanism, blending local tradition with global modernism. After the revolution, much of this cultural flowering was suppressed, but Volume 4 survived as testament, becoming a beacon for later generations.

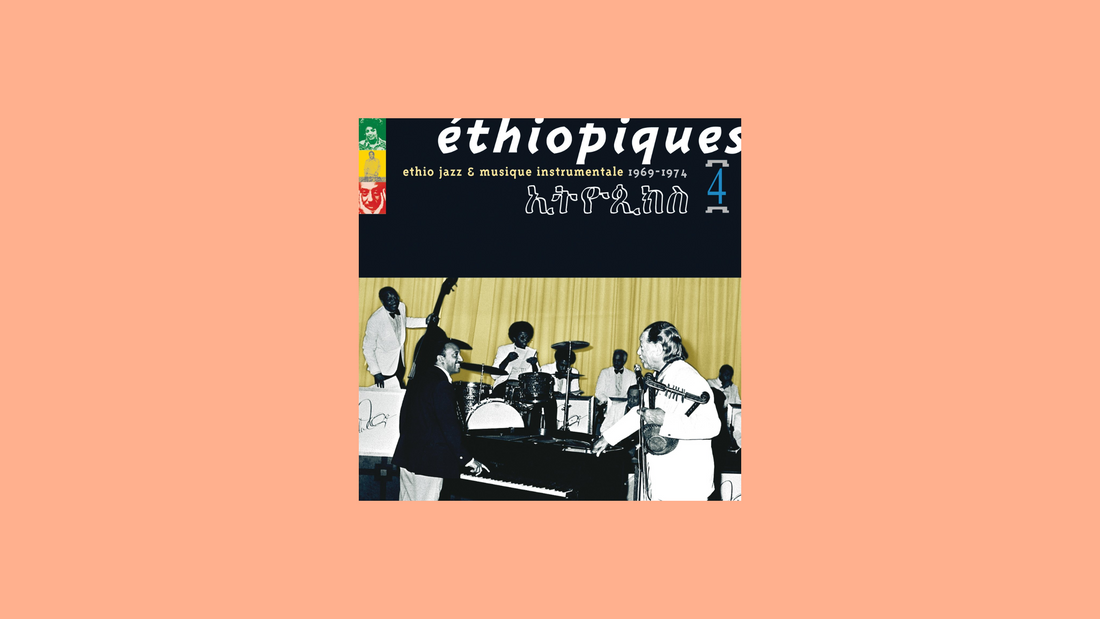

Rediscovered internationally in the 1990s and 2000s through compilations like Éthiopiques, the album influenced artists far beyond Ethiopia. From Jim Jarmusch films to hip-hop samples, from jazz revivalists to electronic producers, its sound has echoed across continents. It showed that Ethiopian modes could sit alongside funk, jazz, and ambient, that Addis had its own claim on the global soundscape.

Listening today, the album feels both timeless and timely. Its grooves are steady and accessible, its melodies unforgettable. You do not need to know about qenet or Ethiopian history to be drawn in. The sound is immediately captivating. Women and men, new listeners and seasoned jazz devotees alike, find themselves at home in its atmosphere. Its inclusivity lies in its balance: serious but not forbidding, deep but never dense.

On vinyl, the record glows. The analogue warmth amplifies the vibraphone’s shimmer, the bass’s depth, the horns’ plaintive cry. The surface crackle blends with the music’s smoky texture, as though recorded in a club half-lit by candlelight. The sleeve, with its austere typography and portrait of Astatke, reinforces the sense of both local pride and global ambition.

Nearly fifty years on, Ethiopian Jazz Volume 4 remains the defining statement of Ethio-jazz. It is not just a historical artefact but a living, breathing sound, still sampled, still performed, still listened to. It proves that local traditions can be modernist, that jazz can be African in voice as much as American, that listening can be both deep and welcoming.

To play this record today is to step into a different atmosphere: slow, smoky, modal, hypnotic. It is to hear Addis at its most creative, Astatke at his most inspired, jazz at its most borderless. It is to hear music that does not just cross cultures but creates a new one.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.