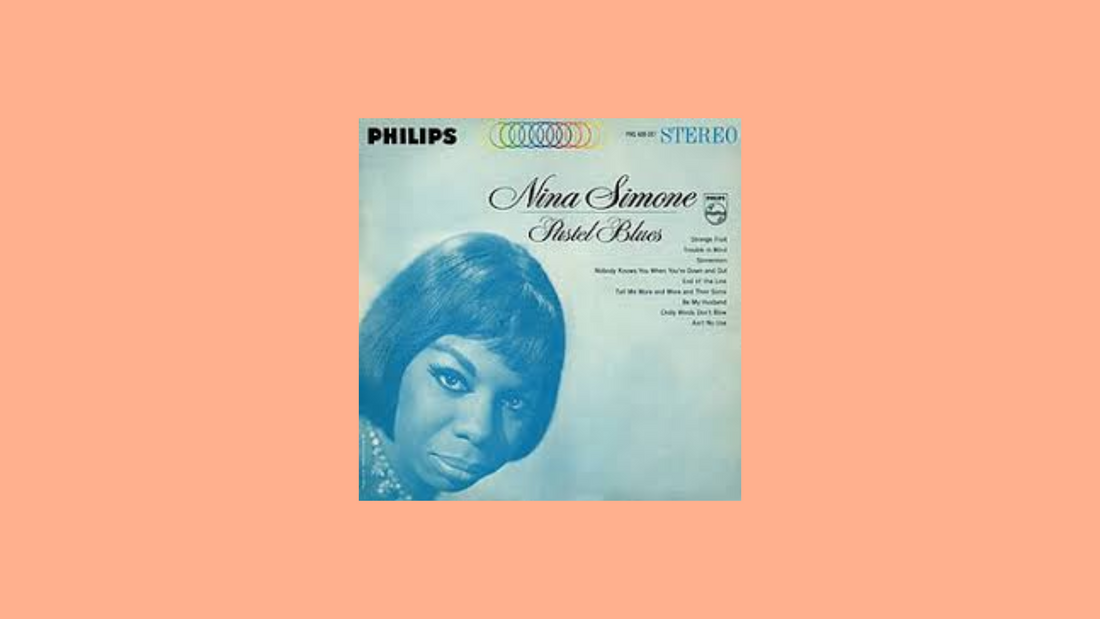

Nina Simone – Pastel Blues (1965)

By Rafi Mercer

The piano chords arrive like footsteps, deliberate and unhurried. Then Nina Simone’s voice enters: low, commanding, edged with steel. It is not the sound of someone asking to be heard. It is the sound of someone who expects to be listened to. Pastel Blues, released in 1965, is one of Simone’s most searing albums — a record that strips the blues to its essence, where every note carries the weight of lived experience.

The title is deceptive. There is nothing pastel about these performances. They are bold, saturated, at times almost unbearable in their intensity. Across ten tracks, Simone moves through gospel, folk, and blues standards, yet she transforms them entirely. They are not covers but confrontations, her interpretations charged with a sense of inevitability. Once you hear them this way, it is hard to imagine them otherwise.

The opening track, “Be My Husband,” is stark. Just Simone’s voice, accompanied by handclaps and a tambourine played by her husband Andy Stroud. She sings the plea as command, turning the traditional roles of gender on their head. Her voice is both intimate and unyielding, sensual and fierce. It is an invocation of desire but also a rewriting of power.

“Tell Me More and More and Then Some” follows with sultry swing, Simone leaning into the phrasing with both humour and ache. “Trouble in Mind,” a blues standard, becomes something entirely hers — her piano steady, her voice stretching the melody until it aches with resignation. “Chilly Winds Don’t Blow” carries gospel warmth, a hymn of resilience.

The centrepiece, however, is “Sinnerman.” At over ten minutes, it is epic, relentless. Simone’s piano pounds with gospel fury, her voice rising in waves, repeating the title phrase until it becomes incantation. The track builds and builds, call and response echoing like a congregation, percussion intensifying until the listener is swept into its vortex. It is not just performance; it is ritual. Few recordings in popular music carry such raw, unmediated power.

Elsewhere, “End of the Line” is fragile, tender, reminding us that Simone could be as vulnerable as she was fierce. “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” is sung not with resignation but with wry wisdom, her delivery balancing humour and lament. The album closes with “Strange Fruit,” the harrowing anti-lynching song first made famous by Billie Holiday. Simone’s version is stark, unflinching, her piano chords tolling like funeral bells. Her voice is controlled, almost restrained, but that restraint makes the horror all the more palpable.

What makes Pastel Blues so extraordinary is Simone’s ability to hold contradictions. Her voice is at once beautiful and abrasive, her interpretations both faithful and revolutionary. She makes the blues feel less like genre and more like condition: a state of being, a way of surviving. There is nothing ornamental here. Every note has purpose, every silence weight.

In 1965, the album’s release carried particular urgency. The Civil Rights Movement was at its height, and Simone herself was becoming increasingly outspoken in her activism. While Pastel Blues does not feature overt protest songs (with the exception of “Strange Fruit”), its very tone is political. To hear a Black woman sing with such authority, such defiance, such control, was itself a radical act.

Listening today, the album has lost none of its power. If anything, it has grown more resonant. In a music culture often smoothed into polish, Simone’s rawness feels bracing, necessary. She demands slow listening, attentive listening. These are not tracks to play casually in the background. They are performances to sit with, to be confronted by, to be altered through.

For women in particular, Pastel Blues carries a special charge. Simone reclaims space, redefines desire, resists expectation. Her presence is unapologetic, her authority unassailable. She opens the door not by invitation but by insistence — and in doing so, she makes it possible for others to walk through. For men, too, the album is revelatory: a chance to hear power voiced differently, to learn from a voice that does not soften itself for approval.

On vinyl, the intensity deepens. The analogue warmth cannot soften Simone’s piano, which strikes like hammer on iron. The surface crackle only adds to the intimacy, as if you are sitting in the room with her, the air vibrating with tension. The sleeve, with Simone gazing sideways, half-shadowed, captures the duality: vulnerable, watchful, indomitable.

Nearly sixty years on, Pastel Blues remains a touchstone. Not because it is easy to listen to, but because it is not. Its beauty lies in its demand. Nina Simone asks us not only to hear her but to reckon with what she sings: the weight of history, the persistence of suffering, the fire of resistance, the tenderness of survival. It is music that shakes walls, hearts, and certainties.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.