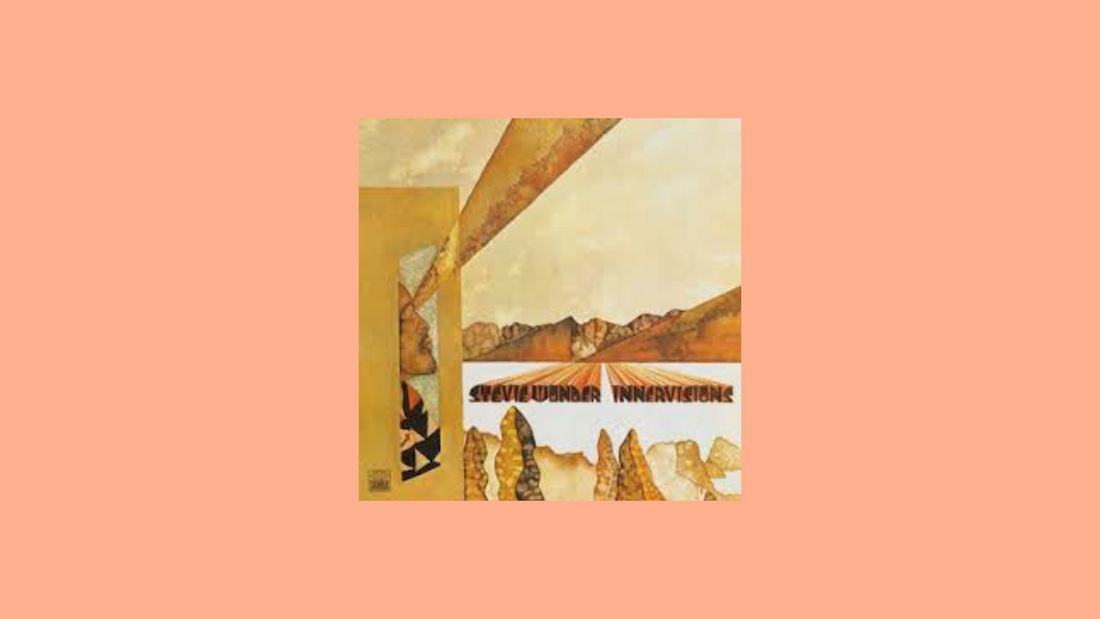

Stevie Wonder – Innervisions (1973)

By Rafi Mercer

The clavinet enters first: sharp, percussive, funky as a city street at rush hour. Then comes Stevie Wonder’s voice, urgent and soaring, calling out injustice with rhythm and grace. “He’s Misstra Know-It-All…” With Innervisions, released in 1973, Stevie Wonder cemented his place not only as one of the greatest songwriters of his generation but as a visionary — an artist who could weave funk, jazz, soul, and political critique into a seamless whole. This was not just pop music. It was prophecy set to groove.

By the early 1970s, Wonder had wrestled creative control from Motown, signing a landmark contract that gave him the freedom to experiment. The result was a run of albums — Music of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions, Fulfillingness’ First Finale, Songs in the Key of Life — that remain unparalleled in ambition and brilliance. Among them, Innervisions stands out for its clarity of vision: nine tracks that capture the turbulence of America in the early ’70s while radiating spiritual hope.

The album opens with “Too High,” a warning wrapped in irresistible funk. Wonder uses his own voice layered through a vocoder-like effect, creating a psychedelic swirl over bass and drums. It critiques drug use, but without sanctimony. The groove pulls you in even as the message sobers you.

“Visions” follows, a quiet ballad where Wonder plays acoustic guitar and sings of dreams deferred. Its tenderness balances the record’s urgency, showing that political critique can coexist with intimacy. Then comes “Living for the City,” perhaps the album’s most powerful statement. Over a relentless groove built from Moog bass and drum machines, Wonder narrates the story of a young Black man moving from Mississippi to New York, only to be crushed by systemic racism. The song includes a dramatic spoken interlude: sirens, footsteps, prison gates. It was revolutionary — not just a song, but a miniature drama, a protest embedded in funk.

Side two brings more variety. “Golden Lady” is pure joy, a love song lifted by Latin rhythms and swirling keyboards. “Higher Ground” pulses with funk urgency, Wonder’s Clavinet riff among the most iconic in music history. The song, written just before the car accident that nearly killed him, speaks of reincarnation, second chances, the urgency of living right. Its groove is irresistible, its message transcendent.

“Jesus Children of America” is gospel for the street corner, calling out hypocrisy with both compassion and fire. “All in Love Is Fair” is an elegant piano ballad, reminding us of Wonder’s melodic gifts. And “He’s Misstra Know-It-All,” the closer, is sly and satirical, aimed at political leaders who manipulate with charm but lack substance.

What makes Innervisions so extraordinary is its balance. It is deeply political but never loses its groove. It is spiritual without preaching. It is joyous even in its critique. Wonder manages to fuse synthesisers, drum machines, and traditional instruments into a sound that feels both futuristic and organic. The album sounds as fresh now as it did in 1973, its themes sadly still relevant.

The cultural impact was immediate. Innervisions won the Grammy for Album of the Year, cementing Wonder’s status as not just a pop star but a cultural prophet. It influenced musicians across genres, from funk and soul to rock and hip-hop. “Living for the City” alone became a template for socially conscious music, its storytelling blending seamlessly with groove.

Listening today, what stands out is Wonder’s inclusivity. His music does not gatekeep. It speaks to everyone — men and women, young and old, rich and poor. His voice is tender enough to reach the heart, fierce enough to call out injustice, joyous enough to make you dance. He shows that funk can be spiritual, that protest can be melodic, that listening can be both pleasure and awakening.

On vinyl, the record is luminous. The warmth of the pressing suits Wonder’s layered keyboards and synthesised bass, each groove vibrating with analogue richness. The transitions between songs feel natural, the sequencing deliberate. The artwork — a surreal portrait of Wonder, eyes closed, head tilted towards the sun — reinforces the album’s essence: vision not as sight, but as inner truth.

Fifty years on, Innervisions still asks us to listen differently. It demands that we move our bodies but also our minds. It shows that music can be both sanctuary and call to action. And in Stevie Wonder’s hands, it proves that groove itself can be prophetic.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.