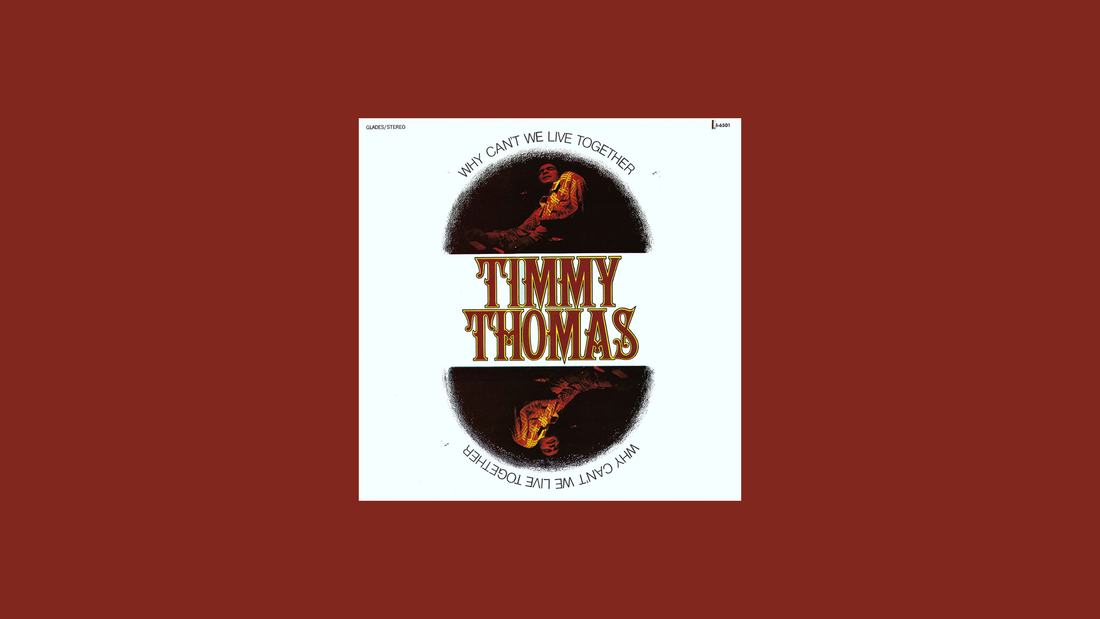

Why Can’t We Live Together – Timmy Thomas (1972)

Timmy Thomas’s Why Can’t We Live Together (1972) is soul stripped to its essence — organ, drum machine, and one human voice.

By Rafi Mercer

Sometimes a song doesn’t just play; it pauses the world for a few minutes. Why Can’t We Live Together was one of those. Released in 1972, it sounded like nothing else — sparse, spacious, and deeply sincere. Just a Hammond organ, an early rhythm machine, and a voice asking one of the oldest questions we still haven’t answered.

I first heard it on vinyl, late one night, and couldn’t believe how bare it was. No bassline, no guitar, no orchestra — just heartbeat percussion and tone. Every sound is necessary, nothing decorative. It’s one of those records that reminds you how little you actually need to make something honest.

Timmy Thomas recorded the entire album with almost no accompaniment. He was a session musician from Indiana who’d worked in Miami, a man trained in R&B and gospel, but with a producer’s ear for space. What he created wasn’t soul in the conventional sense; it was something leaner, more elemental. The drum machine ticked like a metronome for conscience. The organ shimmered in simple phrases. And over it, his voice — direct, aching, human — asked, “No more wars, we want peace in this world.”

The title track became a global hit, reaching audiences far beyond the soul charts. But the rest of the record carries the same quiet conviction. “Rainbow Power” hums with optimism; “Funky Me” pulses with meditative rhythm. Even the instrumentals feel devotional, built on repetition that feels closer to prayer than performance.

What makes the album extraordinary is how modern it still sounds. The minimal drum programming — just a box ticking time — became an ancestor of every machine rhythm that followed: Prince, Sade, Massive Attack, even Drake. (He famously sampled the title track decades later for “Hotline Bling.”) You can hear Timmy Thomas’s DNA running through half a century of electronic soul. Yet he did it with less than anyone else — a man alone in a studio, working with instinct and conviction.

Through a good system, the record sounds startlingly present. The drum machine sits high in the mix, crisp and dry. The Hammond swells and recedes like breath. The vocal — imperfect, tremulous — lands in the room as if he’s still asking you directly. There’s no studio gloss, no reverb to hide behind. You hear humanity in its rawest frequency.

Rafi would call this the architecture of compassion — design through simplicity. Every note serves purpose, every silence serves clarity. It’s music made from faith in the listener, faith that the truth will resonate louder than any arrangement.

The early 1970s were loud with politics, yet Thomas’s protest was whisper-soft. While others marched through distortion, he sat at an organ and played calm into chaos. That’s the courage of this record — gentleness as resistance. It didn’t posture; it persuaded.

Songs like “People Are Changing” and “The Coldest Days of My Life” extend that idea. He doesn’t lecture, he observes. The phrasing is conversational, almost humble. You can sense the gospel roots — not in style, but in spirit: the belief that sound can heal if you let it breathe.

Half a century later, it still feels personal. Its imperfections are its power. When the drum machine stutters or the organ slightly detunes, it feels more alive — proof that precision isn’t the same as truth. Through headphones, you can hear the tiny static of the tape, the hum of the room. It’s like time itself is still running in the background.

And there’s something quietly radical about the question he asks. Why can’t we live together? It’s so simple, it’s almost painful. The line has no metaphor, no poetry to hide behind. It’s direct, almost childlike, and that’s why it endures. Because simplicity, when honest, cuts deeper than sophistication.

When you step back, the whole record feels like one extended meditation on empathy — a one-man version of what would later be called minimal soul, or even proto-electronic gospel. There’s no genre to contain it. It’s just sound as conscience.

Listening today, in an age of overproduction, it feels more urgent than ever. Why Can’t We Live Together isn’t just a song title — it’s a manifesto for restraint, for grace, for the possibility that a single rhythm can hold a moral truth.

The closing moments fade without ceremony. The machine keeps ticking, the organ sighs, and then silence. It’s as if he’s handed the question back to you.

And maybe that’s the point — that we were never meant to answer it in words, but in how we listen.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters.

For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.