Why Japanese Vinyl Still Matters: Imports, Listening Bars, and the Art of Sound

By Rafi Mercer

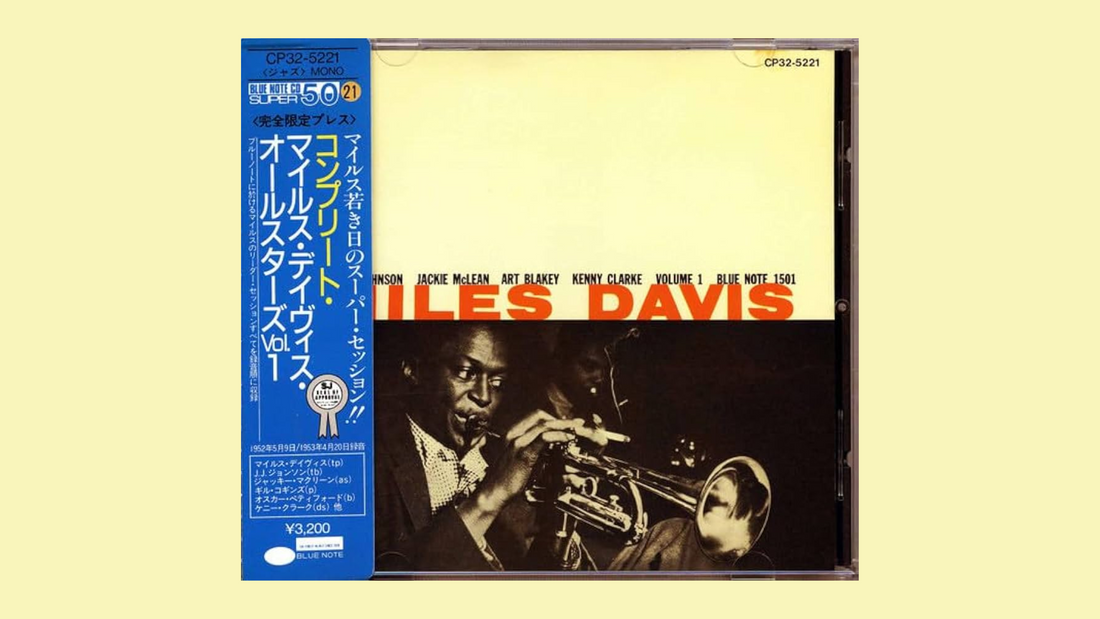

The first time I handled a Japanese pressing, it was obvious: this was not just a record, it was an artefact. The sleeve had weight, the paper stock carried texture, the obi strip wrapped around it like a seal of authority. Slide the vinyl from its sleeve and the difference continued — quieter surfaces, deeper grooves, an almost obsessive attention to fidelity. These were records made with reverence.

During my years at Virgin, I bought a lot of jazz imports, particularly those limited-edition Japanese vinyl reissues. At the time, I thought of them simply as product: something that collectors craved, that elevated the seriousness of the store’s catalogue. But looking back now, with the knowledge of Japan’s listening bar tradition, I realise those imports were part of something bigger. They were not just commodities. They were expressions of a culture that believed listening was an art form in itself.

In post-war Japan, jazz was more than music; it was aspiration, escape, communion. The kissaten cafés became sanctuaries where imported records were played at near-concert volume, the speakers often horn-loaded, the etiquette monastic. Silence was enforced, attention demanded. The records themselves became sacred objects, chosen with care, handled with ceremony. In that context, it makes sense that Japanese pressings acquired a reputation for perfection. If listening was going to be treated as ritual, then the medium had to be immaculate.

The engineering justified the reverence. Japanese pressing plants used higher-quality vinyl compounds, resulting in surfaces with less noise. Mastering was often done with a focus on clarity and tonal balance, even on budget jazz titles. The packaging was equally meticulous — heavy card sleeves, inserts with translations and essays, obi strips that added both information and mystique. For collectors in London, New York, Berlin, these pressings felt like talismans: proof of another culture’s devotion to sound.

I watched customers seek them out in the stores. Some wanted the fidelity. Others wanted the scarcity — the thrill of owning something rare. But most, I think, responded instinctively to the aura. Holding a Japanese pressing felt different. It whispered of seriousness, of connoisseurship, of a respect for the music that matched the reverence you felt as a listener.

The connection to listening bars is now obvious to me. Those cafés, with their towering speakers and shelves of carefully curated records, were physical manifestations of the same philosophy that shaped the records themselves: that music deserved respect, space, silence. The import pressing was not an accessory to that culture; it was its currency.

And perhaps that’s why these records still matter today, even in an age of streaming and digital ubiquity. They remind us that sound is not disposable. They embody the belief that the way something is made — the grooves, the weight, the sleeve — shapes how it is heard. They connect us back to a lineage of listening that insists on patience, on focus, on care.

When I think about those years now, surrounded by turntables and stacks of vinyl, I realise how much of that philosophy seeped into me. The Japanese imports I bought for the stores were more than stock. They were fragments of another culture’s devotion to music, fragments that have since spread worldwide, influencing the rise of listening bars in Europe and America, inspiring a generation to listen differently.

Today, as I lower the needle onto one of those pressings — perhaps a Miles Davis reissue, its sleeve still crisp after decades — I can hear the continuity. Not just the music, but the craft, the ethos, the insistence that sound deserves space. The vinyl itself carries that history, each groove etched with a belief that listening is not background, but foreground; not pastime, but philosophy.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe here, or click here to read more.