The Temperature of Music

Warmth, coolness, and the physical climate of sound.

By Rafi Mercer

Every room has a temperature, and every sound a climate. You can feel it before the music begins — in the weight of the air, in how breath condenses or disappears, in the way a note either glows or glints. Warmth makes music bloom; coolness gives it shape. Together they form the emotional weather of a space.

How temperature shapes listening:

- Warmth softens edges — low frequencies expand, voices feel closer.

- Coolness clarifies — highs shimmer, detail stands apart.

- Humidity holds sound — dry air scatters it; moisture makes it round.

- Season defines timbre — winter light thickens tone, summer air thins it.

- Touch and tone align — the body’s comfort mirrors the ear’s response.

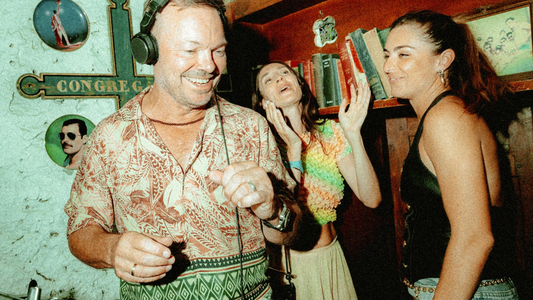

In the best listening bars, climate control isn’t functional — it’s aesthetic. A degree or two either way changes the room’s whole energy. Too cold, and conversation becomes brittle, posture tightens, bass loses weight. Too warm, and the mix turns syrupy, focus fades. The aim is balance: an atmosphere that feels alive, not inert.

The Japanese understood this instinctively. In summer, kissaten owners played lighter records — brushed drums, flutes, bossa nova — and cooled the air to match. In winter, they slowed everything down: Coltrane, Mingus, whisky, heat. The temperature set the tempo.

Sound engineers speak of warmth in tone, but the metaphor is literal. Tube amplifiers glow for a reason — not only visually, but sonically. The heat they produce enriches harmonics, adding a soft bloom around notes. Digital precision is cooler, more analytical, and sometimes that clarity suits the mood. The trick is to feel which temperature the evening wants.

At home, the same principle applies. A warm room invites long play — records in sequence, whisky slow. A cool room sharpens attention — ideal for minimalism, electronica, or early morning jazz. The goal isn’t comfort for its own sake; it’s coherence between climate and sound.

Temperature, like tone, is emotional calibration. You sense when it’s right. The glass sweats slightly; the light sits low; the record breathes easily. Warmth and coolness become partners in the art of listening — two forms of air, tuned for feeling.

Because music doesn’t just travel through space — it travels through climate. And when both align, the room becomes weather.

Quick Questions

Does temperature really change how we hear?

Yes. The air’s density, humidity, and heat all affect how sound waves move — and how we perceive mood.

Why are tube amps described as “warm”?

Because their harmonic distortion and physical heat produce a richer, rounder tone.

What’s the ideal climate for a listening room?

Around 20°C with moderate humidity — cool enough for clarity, warm enough for ease.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters.

For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.