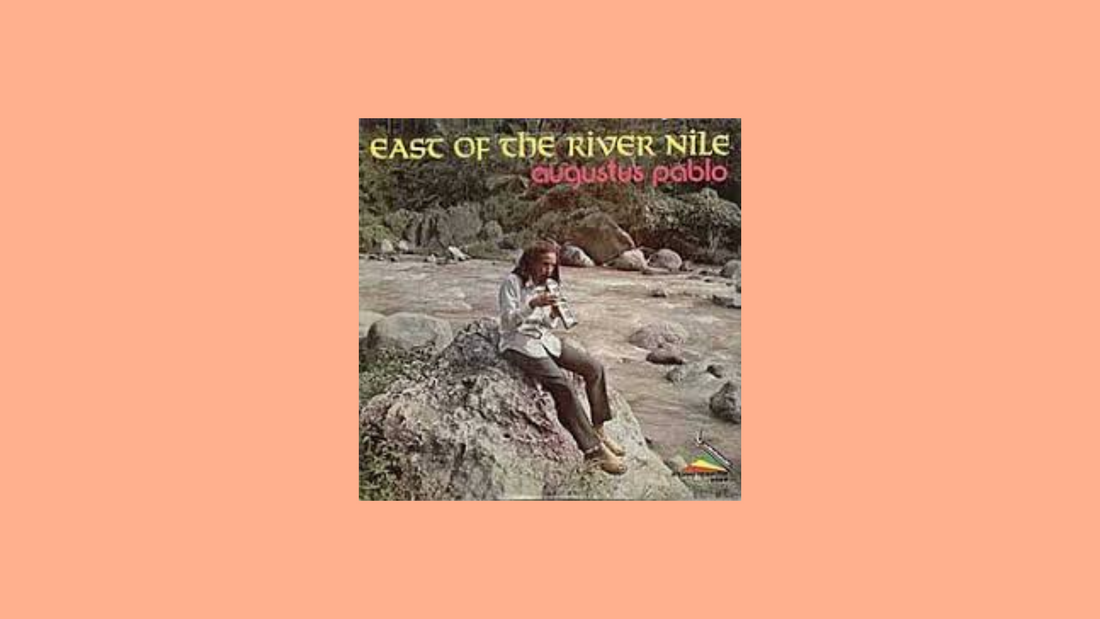

Augustus Pablo – East of the River Nile (1977)

By Rafi Mercer

The melodica is an unlikely instrument for prophecy. A small, plastic keyboard blown through like a child’s toy, it was never intended for serious music. Yet in Augustus Pablo’s hands, it became something sacred — a voice as plaintive and searching as any horn. Nowhere is this clearer than on East of the River Nile (1977), his masterpiece, where the melodica carries reggae and dub into uncharted spiritual terrain. The record remains a cornerstone not only of Jamaican music but of global listening culture: meditative, mystical, and utterly timeless.

Horace Swaby, better known as Augustus Pablo, was already a unique presence in the 1970s Kingston scene. Tall, thin, deeply reserved, he seemed less a performer than a channel, a vessel for sound. His melodica style had made him instantly recognisable on singles like “Java,” but East of the River Nile expanded his vision. This was not just an album of instrumental reggae. It was a manifesto of sound as meditation, as resistance, as inner journey.

The title track sets the tone immediately. Over a deep, rolling rhythm laid down by the legendary Rockers All Stars (including Robbie Shakespeare, Earl “Chinna” Smith, and others), Pablo’s melodica enters like a chant. Its tone is fragile, wavering, yet insistent. The melody is simple, but it cuts straight to the heart, as if ancient and modern at once. Echo and reverb stretch its phrases into the distance, turning them into prayers carried on the wind.

Other tracks deepen the atmosphere. “Upfull Living” pairs melodica with a steady, roots groove, radiating warmth and uplift. “Chant to King Selassie I” is solemn, devotional, every note imbued with reverence. “Addis Ababa” transports the listener into an imagined Ethiopia, where reggae’s rhythms intertwine with spiritual longing. The bass is monumental, but never aggressive; it is foundation, earth, ground. The melodica floats above, like spirit over body.

What makes East of the River Nile extraordinary is its combination of simplicity and depth. The melodica plays childlike lines, almost naive. But through Pablo’s phrasing, through the weight of the rhythm, through the atmosphere of the mix, those lines acquire gravity. They become mantras, repeated until they resonate in the body. The music does not demand analysis. It demands presence.

The album also embodies the essence of dub without being a dub record in the strict sense. Space is everywhere: echoes trailing into silence, instruments dropping in and out, the studio treated as instrument. Yet Pablo’s touch is gentler than Perry’s chaos or Tubby’s starkness. His use of space feels meditative, reflective. He was less interested in spectacle than in atmosphere — in creating a sound world you could live inside.

Culturally, the record was groundbreaking. It solidified Pablo’s role as one of reggae’s most innovative figures, and it broadened the reach of dub. For many listeners outside Jamaica, East of the River Nile became an entry point — a record that carried reggae’s roots into a universal spiritual dimension. It has since influenced not only reggae musicians but ambient artists, electronic producers, and anyone interested in the intersection of rhythm and meditation.

Listening today, the album feels as relevant as ever. In an age of distraction and speed, its patience is radical. It asks nothing more than stillness: to sit, to listen, to breathe with it. Its melodies are not complex, but they linger. Its grooves are not flashy, but they endure. It is music that opens space — for thought, for reflection, for connection.

For women and men alike, seasoned listeners or those new to reggae, East of the River Nile is welcoming. There is no bravado, no gatekeeping. Its strength lies in humility, in the fragility of the melodica’s voice. It says: music need not be loud to be powerful, need not be complex to be profound. It offers a vision of sound as sanctuary, available to anyone who chooses to enter.

On vinyl, the record becomes especially resonant. The bass rolls through the floor, grounding you. The melodica hovers above, fragile yet persistent. The faint crackle of the pressing merges with the echoes, as if the record itself were breathing. The artwork — Pablo standing solemnly with melodica in hand — reinforces the sense of devotion. This is not music for distraction. It is music for ceremony.

Nearly fifty years on, East of the River Nile stands as one of the great albums of listening culture. It bridges roots reggae and dub, local and global, body and spirit. It proves that even the humblest of instruments can carry profound weight if played with sincerity. Pablo took a child’s toy and turned it into a vessel of prophecy.

To listen today is to be reminded that the deepest journeys often begin with the simplest sounds: a breath into a melodica, a bassline rolling like earth itself, a prayer carried into echo.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.