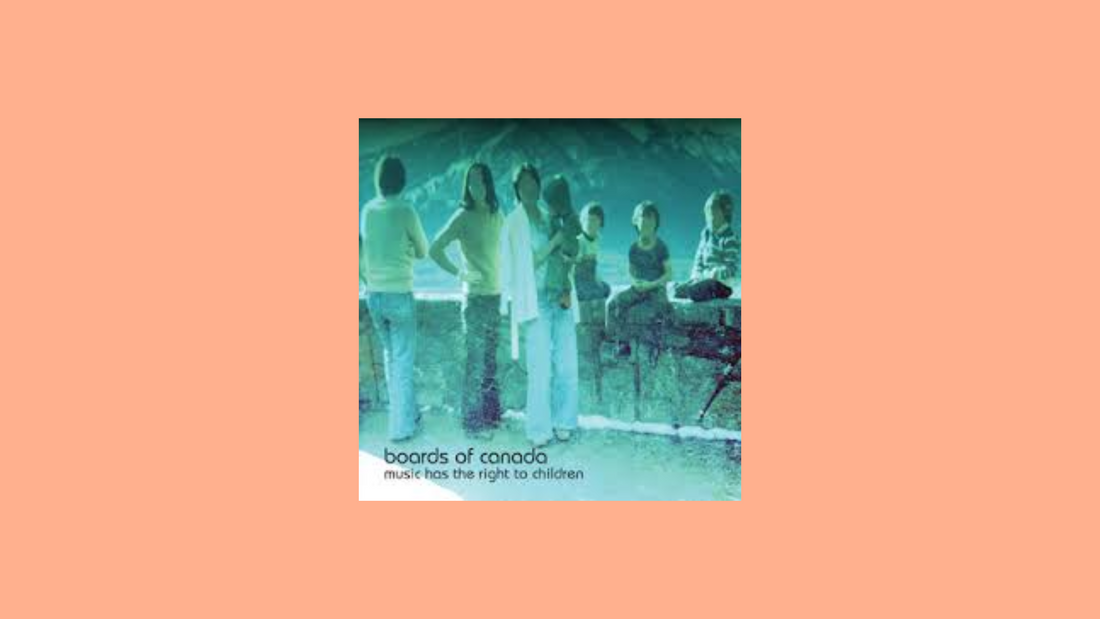

Boards of Canada – Music Has the Right to Children (1998)

By Rafi Mercer

The first thing you notice is the texture: a haze of tape hiss, warping tones, melodies that sound like they have been left in the sun too long. Then comes the rhythm — not polished, not mechanical, but softened, human, as though recorded on worn VHS rather than digital equipment. This is Boards of Canada’s Music Has the Right to Children, released in 1998, and it remains one of the most mysterious, affecting, and enduring albums in electronic music.

Boards of Canada — brothers Marcus Eoin and Michael Sandison — were working in relative obscurity in Scotland before this record appeared on Warp Records. Their sound was unlike anything else on the label, which was then dominated by sharp-edged IDM from acts like Aphex Twin and Autechre. Where others pushed complexity, Boards of Canada leaned into nostalgia, imperfection, memory. They used synthesisers and samplers not to build futuristic structures but to reconstruct the hazy world of childhood, television jingles, nature documentaries, half-forgotten voices.

The album’s title signals its intent: children and memory are central. Yet this is not sentimental music. It is not lullabies or nursery rhymes. Instead, it evokes the feeling of memory — the way recollection is always partial, distorted, tinged with melancholy. Listening is like leafing through old photographs: familiar faces blurred, colours faded, emotions lingering without clarity.

“Wildlife Analysis,” the short opening track, sets the tone with faint melody and background hiss. Then “An Eagle in Your Mind” enters with a dusty hip-hop beat and a drone that seems to stretch into infinity. The track is hypnotic, suggestive of travel — not fast, not urgent, but endless, like watching countryside roll by from a train window. “Turquoise Hexagon Sun” introduces melodic fragments that shimmer and dissolve, never quite coalescing.

The most famous track, “Roygbiv,” is deceptively simple: a short, looping bassline, childlike melody, a groove that could almost be pop. But its brevity — under three minutes — makes it more like a glimpse, a memory flashing before disappearing. “Aquarius” samples a child reciting the months of the year, but loops it until it becomes eerie, uncanny. “Telephasic Workshop” layers scrambled voices over a beat that stutters like malfunctioning tape. Throughout, voices drift in and out, often unrecognisable, often unsettling.

What makes Music Has the Right to Children so distinctive is its use of texture. Boards of Canada deliberately degrade their sounds — detuning synths, warping tapes, adding hiss and crackle. These imperfections become the essence of the record. Unlike the gleaming precision of much electronic music, this album sounds worn, lived-in. It is not about the future; it is about the past, refracted through technology.

The effect is profoundly emotional. For some, it evokes childhood directly — school films, public television, afternoons in front of flickering screens. For others, it evokes memory itself, the way the past is always distorted. Either way, it is deeply human. You do not need to know the references to feel it. Anyone can step into its atmosphere and recognise the sense of longing, the strange mixture of comfort and unease.

The cultural impact was immediate. Critics hailed it as a masterpiece, and listeners embraced it not only within electronic circles but far beyond. It influenced trip-hop, indie rock, ambient, even hip-hop producers. Its sense of atmosphere — of music as environment, as mood — has seeped into countless works since. Yet it has never been imitated successfully. Its combination of warmth, melancholy, and strangeness is too specific, too personal.

Importantly, Music Has the Right to Children feels inclusive. It does not posture as virtuosic or exclusive. Its imperfections make it approachable, its warmth makes it hospitable. For women and men alike, for seasoned collectors or curious newcomers, it offers an entry point into electronic music that is emotional rather than technical. It says: you do not need to understand synthesisers to feel this. You only need to listen.

On vinyl, the textures come alive. The natural hiss of the pressing blends with the artificial hiss in the music, erasing the line between medium and composition. The warmth of analogue playback deepens the bass, making the grooves feel bodily. The act of flipping sides suits the album’s fragmentary nature — each side a different set of memories, glimpses, moods.

What keeps the album alive after more than twenty-five years is its refusal of clarity. It never explains itself. The titles are cryptic, the voices obscured, the melodies fleeting. And yet, precisely because it does not explain, it resonates. It mirrors memory itself: incomplete, fragile, but powerful. It reminds us that listening is not only about sound but about what sound stirs in us — feelings, images, fragments of lives lived.

Boards of Canada may remain enigmatic, rarely performing, rarely speaking. But their music speaks clearly in its own language: nostalgic, haunting, generous. Music Has the Right to Children is more than a record. It is an atmosphere, a room you can step into whenever you need to remember that listening is not only about the present tense, but about all the echoes that linger within us.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.