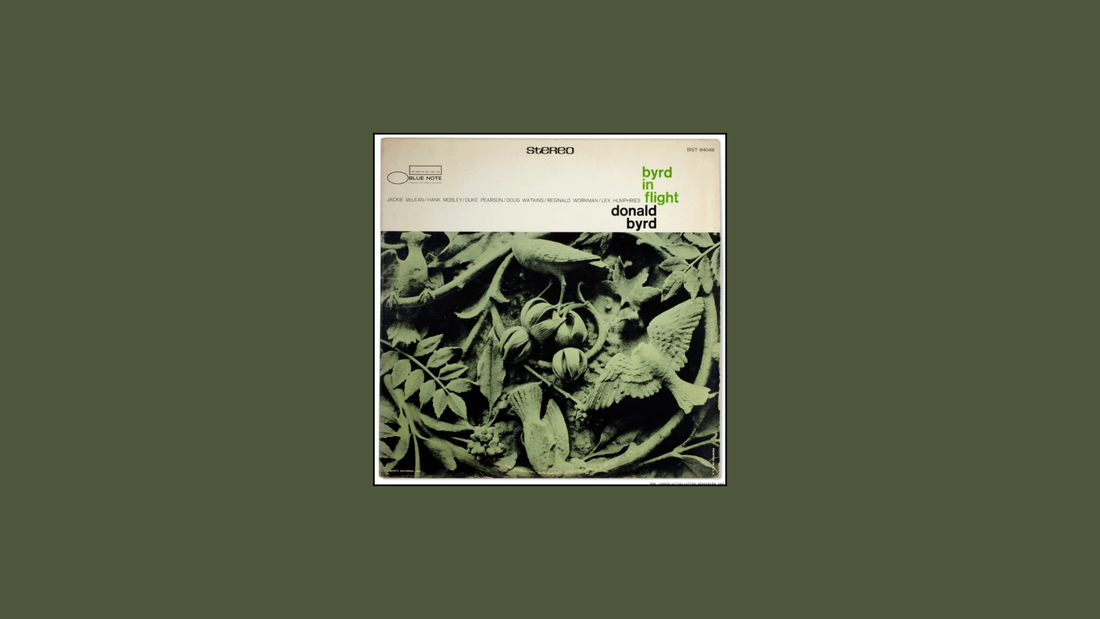

Byrd in Flight – Donald Byrd (1960)

Air and Intention

By Rafi Mercer

There’s a point early in every great artist’s story when the craft is already perfect, but the restlessness has begun. Byrd in Flight, recorded in 1960, sits precisely there. It’s the sound of Donald Byrd before reinvention — crisp, lyrical, swinging hard, yet already searching for new altitude. Even in its title, you can sense what’s happening: the need to move, to lift, to test how high tone and time can travel before gravity pulls them back.

It’s a classic Blue Note set, both in personnel and poise. Byrd leads an ensemble that reads like a who’s who of late-50s hard bop: Jackie McLean on alto saxophone, Hank Mobley on tenor, Duke Pearson on piano, Doug Watkins and Reggie Workman alternating on bass, and Lex Humphries on drums. These players weren’t merely sidemen; they were architects of a sound — a language defined by precision, poise, and propulsion. Byrd in Flight captures that language spoken fluently.

The opening track, Ghana, begins with a snare hit and a quick breath before the horns rise in unison — bright, tight, perfectly balanced. It’s hard bop in full stride: intricate but not academic, earthy yet urbane. Byrd’s solo climbs with measured energy, his tone golden and full, while Pearson’s piano provides both rhythm and reflection. The structure is clean, the swing unforced, and the interplay exact. This was music built like mid-century design — modern, functional, graceful in proportion.

Then comes Little Boy Blue, a ballad that shows Byrd’s lyricism at its peak. The trumpet line feels less like melody and more like storytelling — every note placed as if weighed by hand. There’s warmth, but also restraint. He never overspeaks. McLean’s alto follows with quiet fire, cutting through the mood without disturbing its stillness. Behind them, Humphries’ brushwork is a study in understatement — texture as timekeeping.

Gate City restores momentum, Mobley’s tenor giving it a grounded soulfulness. The horns move together like polished wood — smooth, resonant, unhurried. Byrd leads not as a commander but as a craftsman, building shape through dialogue. There’s a shared humility here, a sense of musicians listening deeply to one another. You can hear it in the transitions — no one trying to dominate, everyone contributing to the flow.

Lex is pure kinetic joy — fast, buoyant, joyful — with Byrd playing phrases that sound like sketches for flight itself. His upper register glints but never pierces. Even when the band burns, the control remains. That’s the paradox of Donald Byrd: the energy of a soloist, the temperament of an architect.

The closing tracks, Bo and My Girl Shirl, are the ones that linger in memory. Bo opens with a rhythmic motif that feels almost anticipatory, a prelude to the modal sensibilities that would later shape Free Form. It’s spacious, forward-leaning, a whisper of what’s to come. My Girl Shirl, on the other hand, is pure Blue Note charm — melody-driven, foot-tapping, full of daylight. It’s the kind of track that makes a bar feel brighter, even at midnight.

In the listening room, Byrd in Flight has a particular clarity — all the signature Van Gelder spatial cues intact. The stereo field breathes; every horn line feels tangible. Through a well-balanced system, you can locate each player precisely in the soundstage: Humphries slightly back and right, Pearson sitting central and low, Byrd a clear, commanding voice just above the mix. It’s music that rewards attention — not through volume, but through balance.

What’s striking about Byrd in Flight now is how contemporary it feels in temperament. Its elegance and discipline would later inspire the same qualities in the best of modern jazz and neo-soul — artists like Robert Glasper, Nubya Garcia, and Makaya McCraven all work in this same geometry: rhythm, line, restraint, release. It’s timeless not because it refuses change, but because it understands proportion.

Culturally, it marked a moment when Blue Note’s house sound was at its most confident. Jazz in 1960 was modernism embodied — the sound of America’s cities building upward, of black artistry claiming its place in the skyline. Byrd in Flight isn’t political on its surface, but it carries the quiet pride of that moment. There’s conviction in its coolness, dignity in its ease.

For Byrd himself, the record was both culmination and catalyst. You can hear him ready to move — not away from this form, but through it. Within a few years he would reach toward gospel (A New Perspective), and a decade later, toward funk (Black Byrd). But those flights wouldn’t have been possible without this clean take-off. Byrd in Flight gave him the runway: control, tone, and balance.

Play it in the bar today and it still clears the air. The trumpet is clear as morning light; the rhythm section is supple and steady; the horns breathe in unison. It’s music that makes conversation sharper, drinks slower, and the room more focused. Not loud. Not soft. Just right.

It’s called Byrd in Flight, but the miracle is that it never loses contact with the ground. The lift comes from proportion — not escape. And that’s the essence of Donald Byrd’s early genius: the ability to make motion feel calm, to make precision feel free.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.