David Bowie – Low (1977)

By Rafi Mercer

A drum machine ticks like a nervous heartbeat. A guitar line flickers, sharp and skeletal. Then David Bowie’s voice enters — flat, cool, distant — singing of dislocation and unease. This is Low, released in 1977, the first of Bowie’s celebrated “Berlin Trilogy,” and one of the most radical turns in his career. Where others would have followed the global success of Station to Station with something grander, Bowie instead turned inward, creating a fractured, minimalist, avant-garde record that reshaped the landscape of rock.

The context was crucial. By 1976, Bowie was exhausted. Years of cocaine addiction, relentless fame, and the demands of stardom had left him close to collapse. Moving to Berlin with Iggy Pop, he sought both anonymity and renewal. There, with producer Tony Visconti and collaborator Brian Eno, he immersed himself in the city’s stark modernism, in its cabaret past and Cold War present, in the experimental sounds of Krautrock groups like Kraftwerk and Neu!. Low is the sound of that immersion — alien, fractured, but deeply alive.

Side one is filled with short, jagged songs, most under four minutes. “Speed of Life” opens with a burst of synths and rhythm, almost instrumental, a statement of reinvention. “Breaking Glass” is sharp and claustrophobic, its lyrics fragmented. “Sound and Vision” is the most accessible, with its buoyant melody and saxophone lines, yet even here Bowie delays his vocal until halfway through, subverting pop structure. “Always Crashing in the Same Car” is weary, resigned, a metaphor for self-destruction. “Be My Wife” is blunt, almost desperate: its plea direct, its delivery detached.

Then comes side two, where the album transforms. Here, Bowie and Eno abandon song form altogether, creating long, atmospheric instrumentals. “Warszawa” is the centrepiece: mournful synth drones, funereal tempo, wordless vocal chants. It is one of Bowie’s most haunting works, evoking not only the divided city but also an inner desolation. “Art Decade,” “Weeping Wall,” and “Subterraneans” continue in this vein — layered textures, minimal rhythm, ambient atmospheres. They owe as much to modern classical music and ambient as to rock.

What makes Low extraordinary is its fragmentation. Side one is all sharp edges, short bursts, unresolved phrases. Side two is all space, long tones, unresolved emotion. Together, they mirror Bowie’s state at the time: fractured, uncertain, searching. But they also anticipate the future. The structure — pop on one side, ambient on the other — was radical then, but has since become prophetic, foreshadowing everything from post-punk to electronic minimalism.

Initially, the record baffled listeners and critics. RCA was dismayed. The songs were too short for radio, the instrumentals too strange for rock. Yet over time, its influence grew immense. Joy Division, Radiohead, Nine Inch Nails, countless electronic artists — all owe something to Low. It demonstrated that a rock star could deconstruct himself in public, could embrace experimentation without abandoning emotion, could reinvent not through excess but through reduction.

Listening today, Low feels as relevant as ever. Its unease mirrors our own fractured modernity. Its openness to silence, to texture, to non-song structure feels in step with contemporary listening habits. Yet it is also inclusive. For all its strangeness, its grooves are steady, its melodies memorable, its atmosphere immersive. It does not gatekeep. It offers entry points: a pop hook here, a haunting drone there.

For women and men alike, the album offers something rare in rock: vulnerability without sentimentality. Bowie does not posture here; he admits fracture, unease, longing. His voice, often distant, carries fragility as much as cool. It is a record of survival, of piecing oneself together, of acknowledging the cracks. That openness makes it hospitable to listeners across divides.

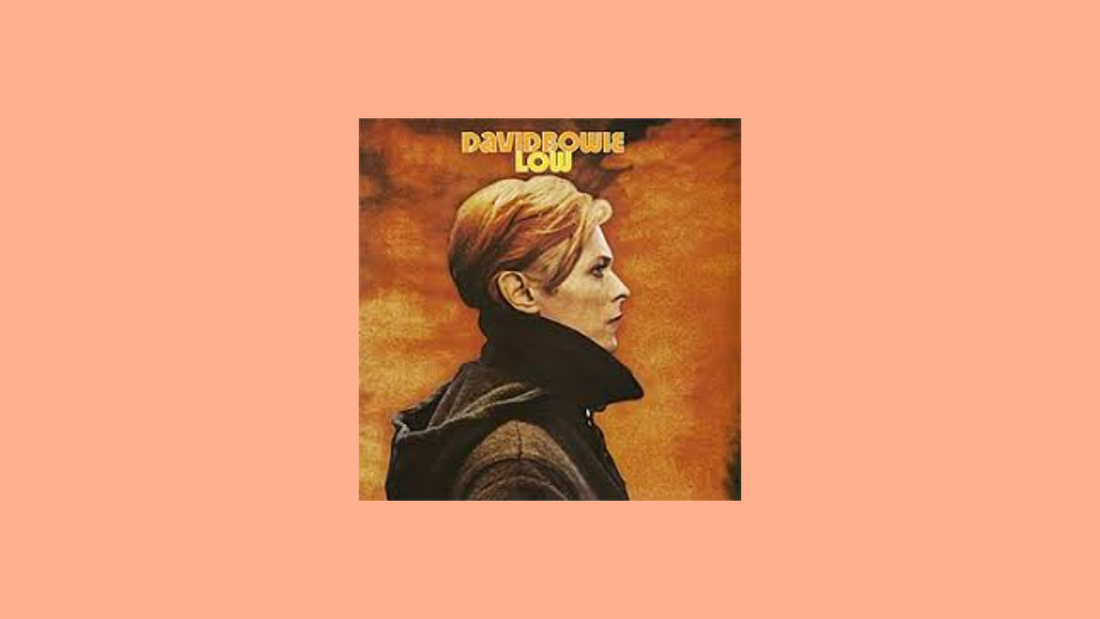

On vinyl, the dual structure is heightened. Side one’s quick cuts force you to flip quickly, while side two’s expanses reward patience. The analogue warmth deepens the synths, making them less brittle, more enveloping. The cover — Bowie in profile, orange background, frozen mid-motion — captures the album’s essence: both iconic and incomplete, present and absent, fractured and enduring.

More than forty-five years on, Low still sounds ahead of its time. It shows that reinvention can mean stripping back, that radicalism can mean restraint, that listening can mean sitting with unease. It is not easy music, but it is generous. It gives space, it gives honesty, it gives atmosphere. It is Bowie at his most vulnerable, and therefore at his most human.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.