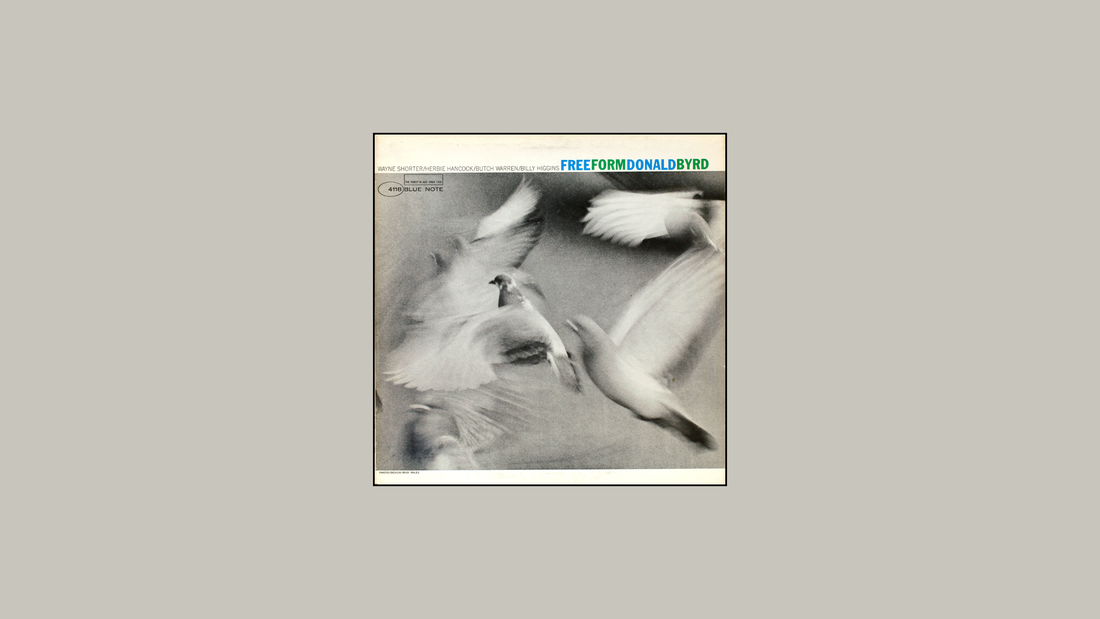

Free Form – Donald Byrd (1961)

The First Crack in the Frame

By Rafi Mercer

There’s a moment in every artist’s life when structure starts to feel like a limitation rather than a comfort. Free Form, recorded in December 1961, catches Donald Byrd right at that turning point. Still working within the elegant geometry of Blue Note hard bop, he’s beginning to loosen the frame — opening doors, testing thresholds, letting air in. The title isn’t just marketing. It’s truth in motion.

Where Royal Flush had the sharp contours of a master builder, Free Form feels like the first crack in the blueprint. The line-up tells you everything: Herbie Hancock returns on piano, Wayne Shorter joins on tenor saxophone, and Herbie Lewis and Billy Higgins hold down the rhythm. This was a forward-looking band — every one of them poised to redefine jazz in their own way within a few short years. Byrd knew it. You can hear him lean into that energy, even as he’s still anchored in craft.

The opening track, Pentecostal Feelin’, is a small revolution disguised as a groove. It starts with a loose gospel vamp, built on Hancock’s tremolo chords and Higgins’ rolling snare. Byrd enters not with bravado but with warmth — full, round tone, lyrical phrasing, a preacher more than a professor. The swing feels organic, unhurried, almost conversational. There’s the scent of church here, but the structure of jazz — call and response without words, release without chaos.

Then comes Night Flower, delicate and restrained. It’s a ballad, but not a conventional one. The melody floats in suspended time, Hancock sketching harmonies that seem to hover more than resolve. Byrd plays with tenderness, his phrasing open and deliberate, while Shorter’s solo bends toward introspection. You can feel the beginnings of that searching tone that would later define his own writing with the Jazz Messengers and Miles Davis.

French Spice is where the temperature rises. It’s an angular composition, its rhythm shifting between swing and Latin inflection, Higgins alternating between bounce and push. Byrd’s solo here is liquid, almost vocal in its phrasing, full of space. Hancock plays like a sculptor, carving light from silence. What’s extraordinary is how modern it still sounds: even six decades on, it feels alert, awake, forward.

The title track, Free Form, is the record’s boldest move. It begins without preamble — a loose, modal pulse rather than a fixed tune. Hancock’s piano clusters create an atmosphere of suspension; Higgins’ cymbals shimmer like static electricity. Byrd doesn’t play to dominate; he plays to explore. His trumpet line moves in arcs and pauses, phrases half-formed, questioning, curious. The ensemble listens intently — it’s collective breathing as much as playing. Nothing here feels choreographed, yet it’s never chaotic. There’s freedom, but also focus.

The closing piece, Three Wishes, returns to melody, giving the listener shape after space. It’s lyrical, slightly melancholic, a gentle landing after flight. The album ends not with finality but with reflection, like a door left ajar.

In the listening bar, Free Form is an album that shifts the air quietly. It doesn’t announce itself. It invites. The tone is warm but contemplative — brass and woodwind softly balanced, cymbals whispering at the edges. Through a high-quality system, the Van Gelder engineering shines: you can hear every brush stroke, every intake of breath, every note decay naturally into room tone. It’s as intimate as a small conversation in a large room.

What makes this record essential isn’t its stylistic daring alone — it’s its emotional intelligence. Byrd doesn’t abandon discipline; he redefines it. You can sense a new kind of listening happening between the players — each phrase a response to the last, each silence a kind of trust. The music breathes. The pulse is human. This is not the cerebral experimentation of later free jazz; it’s intuition given permission.

Historically, Free Form sits at a fascinating intersection. Coltrane was deep into modal exploration, Miles was beginning to deconstruct cool, and Blue Note was quietly supporting artists who wanted to stretch. Byrd didn’t go as far into abstraction as others, but he opened enough of the door for light to pour in. The seeds of his later fluidity — the gospel openness of A New Perspective, the spatial calm of the Mizell years — are all here in embryonic form.

Listening now, it’s striking how much Free Form rewards patience. It’s not a showpiece; it’s a slow reveal. The more time you give it, the more detail emerges — the interplay between Hancock and Higgins, the conversational phrasing of Shorter’s saxophone, the steadiness of Byrd’s tone. It’s music for those who value nuance over noise.

When I play Free Form in the bar, I usually do it early evening, when the crowd’s still thin and the light outside is fading. It’s the kind of record that sets a tone of quiet concentration — a shared hum of thought. There’s rhythm, yes, but it’s contemplative. It makes people lean back, not lean in. It’s the sound of musicians thinking out loud, and somehow, that’s exactly what the room needs sometimes.

Byrd would go on to find fame in brighter, bigger spaces — choirs, funk grooves, studio gloss — but here, in 1961, he’s working with pure material: tone, time, trust. Free Form is the laboratory where his future took shape. It’s the moment he let the air in.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.