Kamasi Washington – The Epic (2015)

By Rafi Mercer

The horns arrive in unison, bold and unflinching, before breaking into a cascade of rhythm and harmony. Drums thunder, bass surges, choirs swell. At the centre of it all, Kamasi Washington’s tenor saxophone declares itself — strong, expansive, full of fire. This is The Epic, released in 2015, a three-hour triple album that reintroduced jazz to a global audience. More than a record, it was a manifesto: jazz as symphony, community, and cosmic journey.

Washington had long been a central figure in Los Angeles’s jazz scene, working with artists like Snoop Dogg, Erykah Badu, and Flying Lotus, while also playing with Kendrick Lamar on To Pimp a Butterfly. But with The Epic, he stepped into the spotlight, presenting a work of extraordinary ambition. Across 17 tracks and nearly 180 minutes, he wove together post-bop fire, funk groove, gospel exaltation, and orchestral grandeur. It was jazz not as niche but as expansive cultural force.

The opening track, “Change of the Guard,” sets the tone: a declaration of intent. A big band of horns plays a surging theme, rhythm section driving hard, choir adding weight. Washington solos with fervour, his tone recalling Coltrane’s spiritual intensity but carrying its own West Coast swagger. From the start, the record insists: this is not background music, not polite jazz club fare. This is music to shake foundations.

Throughout the album, Washington blends influences with ease. “Askim” stretches into modal exploration, bass and drums propelling his improvisation with relentless groove. “The Rhythm Changes” brings in vocals, Patrice Quinn’s soaring voice embodying the album’s spiritual uplift. “Miss Understanding” and “Henrietta Our Hero” showcase his gift for melody, balancing complexity with accessibility.

The scale is astonishing. Strings and choir feature throughout, giving the album symphonic sweep. The rhythm section — including Thundercat on bass, Ronald Bruner Jr. on drums, and Tony Austin on percussion — provides constant propulsion, rooted in funk and hip-hop as much as jazz. The West Coast Get Down, Washington’s long-time collective, forms the backbone, their camaraderie audible in every groove.

What makes The Epic remarkable is not only its ambition but its inclusivity. Despite its length, despite its density, the music feels open, inviting. The melodies are memorable, the grooves infectious, the energy generous. It draws in listeners far beyond traditional jazz audiences — hip-hop fans, electronic heads, classical listeners. Women and men, young and old, seasoned jazz devotees and complete newcomers found themselves equally embraced.

Culturally, the album was seismic. At a time when jazz was often considered marginal, Washington put it back into mainstream conversation. The Epic appeared on year-end lists across genres, played to packed festival crowds, and proved that jazz could once again be a music of mass resonance. It was both revival and reinvention, rooted in tradition but alive to the present.

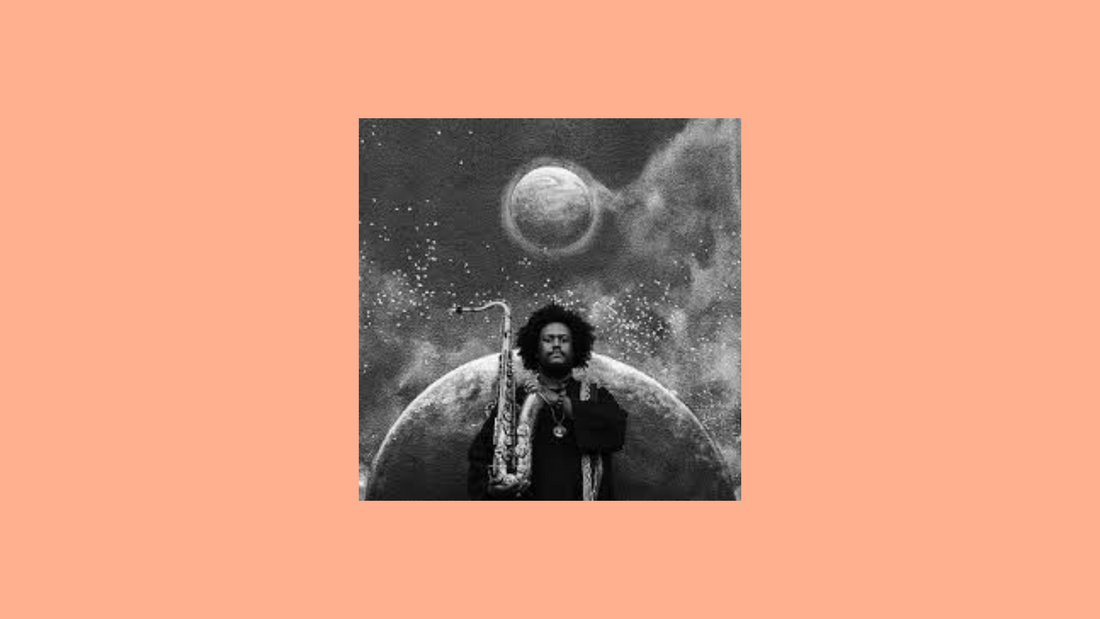

On vinyl, the album’s scale is heightened. The triple LP format makes the listening experience ritualistic: side after side, each with its own arc, each requiring patience and presence. The warmth of the pressing suits Washington’s saxophone tone, the choir’s resonance, the bass’s physicality. The artwork, with Washington depicted in cosmic silhouette, reinforces the record’s ambition: a journey not only through music but through vision.

What endures about The Epic is its generosity. Washington could have made a lean, polished debut. Instead, he gave everything — hours of music, dozens of musicians, a sprawling statement of belief. He proved that jazz could be not only relevant but radiant, not only complex but communal, not only virtuosic but joyful.

To listen to The Epic today is to enter a world of abundance. The horns surge, the choir soars, the drums thunder, the saxophone testifies. It is overwhelming, yes, but also uplifting. It is a reminder that music can be vast without being exclusionary, that ambition can be matched by warmth, that jazz can still change the air we breathe.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.