Lee “Scratch” Perry – Super Ape (1976)

By Rafi Mercer

A low, swampy bassline rolls in, heavy enough to rattle the walls. A snare crack echoes into infinity. Voices call out, sometimes human, sometimes warped into strange, otherworldly tones. At once playful and menacing, cosmic and rooted, this is Lee “Scratch” Perry’s Super Ape. Released in 1976 with his band The Upsetters, it remains one of the most defining dub albums ever made — a record where the studio itself becomes the instrument, and where sound is transformed into myth.

Perry, by the mid-1970s, was already a legend. He had cut his teeth in Kingston as a producer for Coxsone Dodd and Joe Gibbs before striking out on his own with his Black Ark studio. The Black Ark was not a polished facility but a cramped, homemade laboratory. Its equipment was modest, its sound rough, but in Perry’s hands it became a portal. He layered tape effects, reverb, phasing, found sounds, and improvised techniques, turning limitations into magic. Out of this crucible came Super Ape, a record that still feels alive, writhing, unpredictable.

The album is subtitled Heavy Dub, and it earns the claim. The bass is monumental, often leading the charge. The drums, stripped back, are drenched in echo until they seem to reverberate across dimensions. Horns enter and exit like sudden apparitions. Vocals are fragmented, sometimes upfront, sometimes ghostly, sometimes mangled until they sound half-animal, half-machine. Perry was not simply producing tracks; he was sculpting a sonic universe.

“Zion’s Blood,” the opening track, declares its intent immediately. The groove is deep and hypnotic, but Perry’s mixing destabilises it — voices drift in and out, horns are echoed into abstraction, the rhythm seems to stretch and contract. “Croaking Lizard” follows, its vocals pitched down into an amphibian growl, absurd yet strangely powerful. “Dread Lion” pulses with menace, bass and horns circling each other in slow, dubwise ritual.

The centrepiece, “Super Ape,” encapsulates Perry’s myth-making. Over a heavy rhythm, voices chant about the “ape-man trodding through creation.” It is cartoonish, yes, but also mythic, a vision of transformation and power. Perry’s genius was his ability to hold humour and seriousness in the same hand. His records laugh, mock, play — yet they also testify, prophesy, burn.

What makes Super Ape so extraordinary is its sense of atmosphere. This is not simply reggae with the treble turned down. Perry uses echo and reverb to create space, but also to distort time. The listener is suspended in a zone where the ordinary rules of sound no longer apply. Instruments appear, dissolve, reappear in altered form. Vocals are stretched into ghosts. Everyday noises — a cowbell, a whoop, a crackle — are elevated into cosmic signifiers. It is music that feels at once deeply Jamaican and entirely unbound by geography.

The album’s cultural significance is immense. It helped define dub not as a set of remix techniques but as an artform in its own right. Without Perry and albums like Super Ape, the lineage that leads to hip-hop, electronic dance music, and experimental sound design would look entirely different. Dub was not just music; it was philosophy: sound as material, the studio as instrument, rhythm as architecture. Super Ape remains one of its clearest articulations.

Listening today, you hear not just history but vitality. The grooves remain irresistible, the atmosphere intoxicating. Far from sounding dated, the record’s imperfections give it life. The hiss of tape, the grit of the Black Ark’s equipment, the raw edges of the mix — these are not flaws but textures. They remind us that music is not only notes but environment, not only performance but presence.

What is striking, too, is the inclusivity of Perry’s vision. Dub can seem forbidding from the outside, a world of obscure versions and sound system culture. Yet Super Ape is welcoming. Its humour disarms, its rhythms invite. Whether you are a lifelong reggae fan or a newcomer drawn from electronic music, the record opens its doors. Perry himself was irreverent, chaotic, endlessly inventive — and that openness is audible here.

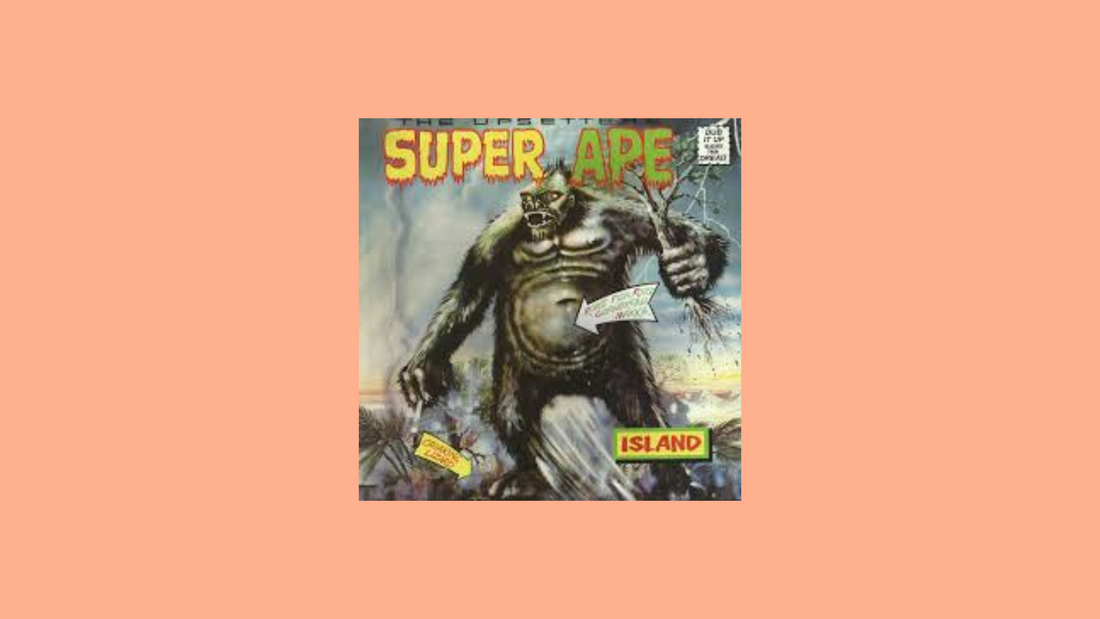

On vinyl, the record’s heaviness is physical. The bass resonates through the floor, the echoes envelop the room. The artwork, with its surreal image of a jungle ape in military garb, amplifies the mythic, comic quality of the music. To play Super Ape on a good system is not simply to listen; it is to step inside Perry’s world, a sonic cartoon that somehow carries the weight of prophecy.

Nearly fifty years on, Super Ape still roars. It is music of roots and wings: grounded in Jamaican rhythm, but flying into cosmic space. It laughs even as it shakes the walls. It shows that experimentation need not be austere, that seriousness can coexist with joy, that listening can be as playful as it is profound. Perry was a trickster, a prophet, a magician of sound. And here, in Super Ape, his vision remains untamed.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.