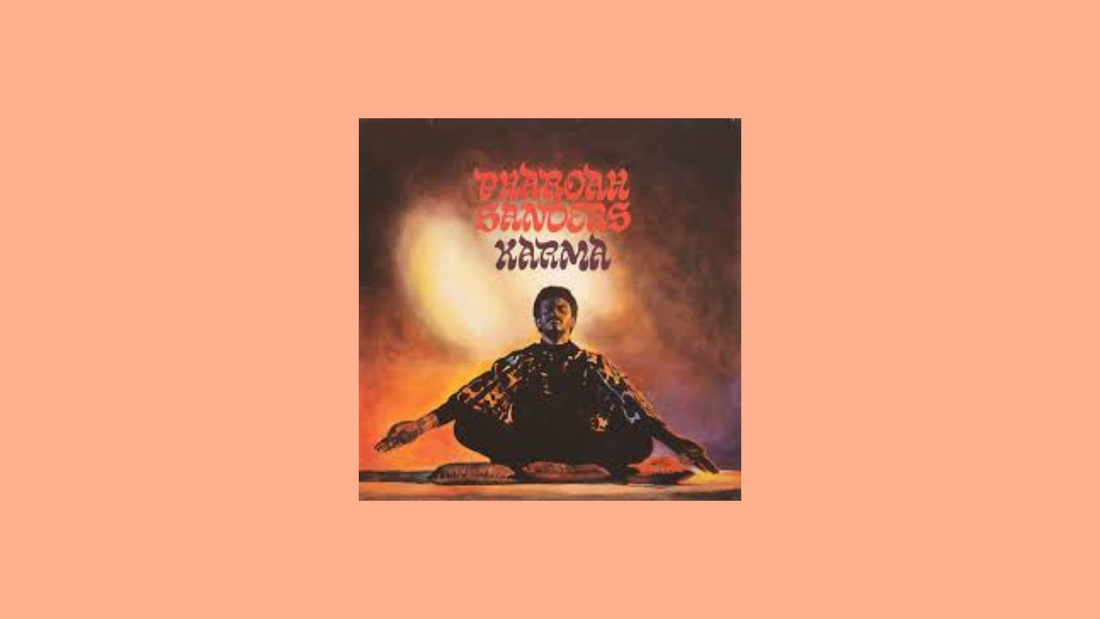

Pharoah Sanders – Karma (1969)

By Rafi Mercer

A gong reverberates, deep and resonant, and then a single theme emerges on the saxophone — urgent, searching, raw. The bass follows, steady as a mantra, while percussion scatters like sparks. Voices join in chant: “The Creator has a master plan…” From the very first moments, Pharoah Sanders’ Karma declares itself not simply as a jazz record but as a spiritual statement. Released in 1969, it remains one of the most iconic works of the so-called “spiritual jazz” movement — a record that insists music can be prayer, meditation, protest, and liberation all at once.

Sanders had made his name in the mid-1960s playing with John Coltrane during Coltrane’s most experimental period. His saxophone sound — searing, overblown, ecstatic — helped push Coltrane’s late ensembles into the realm of the cosmic. But when Sanders recorded Karma, he stepped into his own vision. Here, his fire is balanced by chant, his fury by tenderness, his improvisation by structure. The result is a work both expansive and focused, wild and serene.

The centrepiece is the 32-minute suite “The Creator Has a Master Plan.” Built around a simple bass figure and modal vamp, it unfolds in waves. Sanders’ tenor saxophone leads, alternately lyrical and explosive. Leon Thomas’s voice provides the anchor, chanting the title phrase with earthy conviction, then moving into his trademark yodels — a sound that feels both ancient and futuristic. The piece rises and falls, sometimes furious, sometimes serene, always returning to its mantra.

Listening, you feel less as though you are hearing a composition than participating in a ritual. The repetition is crucial: the bass line, the chant, the drone-like persistence. It is music designed not for quick consumption but for immersion. The groove becomes a vessel, carrying the listener through phases of intensity and release. In its length and patience, it models a different kind of listening — one that values endurance, openness, and surrender.

Side two brings “Colors,” a shorter but no less profound piece. Thomas sings a hymn to beauty and diversity: “The colours of sound, the colours of love…” Sanders’ saxophone is lyrical, tender, almost delicate compared to the fire of side one. It is a reminder that his artistry encompassed not only the ecstatic scream but also the gentle caress. The two tracks together form a cycle: intensity balanced by serenity, protest by affirmation, fire by water.

The cultural context of Karma is essential. Released at the end of the 1960s, in the wake of political upheaval, assassinations, and war, it embodied the search for transcendence that animated much of the Black Arts and Black Power movements. It was a vision of liberation not only political but spiritual. The insistence on a “master plan” was both comfort and resistance — a refusal to be crushed by oppression, a declaration that meaning existed beyond chaos.

Yet what makes Karma remarkable is its inclusivity. The music is demanding — 32 minutes of modal improvisation is not casual listening — but its spirit is welcoming. The mantra is simple, the groove steady, the intention clear. You do not need to be a jazz scholar to enter. You need only to listen with patience. The music does the rest.

For women, men, newcomers, or seasoned jazz heads, the record offers an open door. Its energy is communal, not solitary. You can imagine it as much in a living room as in a temple, as much on a sound system as in a concert hall. It does not gatekeep; it gathers. That gathering quality is what makes it enduring.

On vinyl, the record is especially powerful. The side-long “Creator” fills the room, its grooves pulling the listener into its ritual. The analogue warmth suits Sanders’ saxophone, whose tone is grainy, textured, alive. The surface noise blends with the drones and chants, as if the record itself were part of the ceremony.

Over fifty years later, Karma remains essential. It inspired generations of musicians, from spiritual jazz revivalists to contemporary artists like Kamasi Washington. Its influence can be heard wherever music seeks transcendence through repetition, groove, and improvisation. But its power lies not only in influence. It lies in experience. To put on Karma is to submit to its flow, to be carried through fire and peace, to emerge altered.

Pharoah Sanders was often described as “Coltrane’s disciple,” but Karma proves he was much more: a prophet in his own right, a voice of liberation, a sound of devotion. His saxophone does not simply play; it testifies. And here, in this record, his testimony becomes communal, shared, a ritual anyone can enter.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.