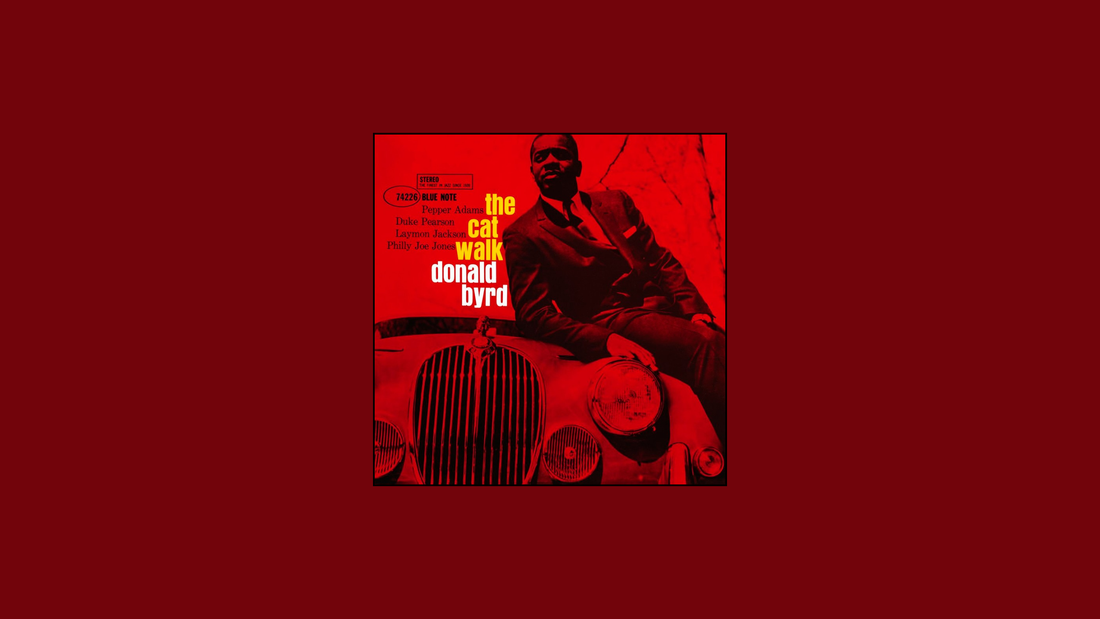

The Cat Walk – Donald Byrd (1961)

Grace in Motion

By Rafi Mercer

Some jazz albums move like they’re in a hurry; others glide, unbothered, self-assured. The Cat Walk glides. Recorded in 1961, it’s Donald Byrd at his most elegant — poised between the tight discipline of hard bop and the looser lyricism that would define his later years. It doesn’t break boundaries; it traces them beautifully. The album walks, not runs, and in its stride you can hear a whole philosophy: calm, grace, and absolute control.

The line-up is pure mid-century Blue Note glamour: Byrd on trumpet, Pepper Adams on baritone saxophone, Duke Pearson on piano, Laymon Jackson on bass, and Philly Joe Jones on drums. This was one of the finest partnerships in post-war jazz — Byrd and Adams had already recorded together extensively, their interplay as tight as any horn pairing of the era. Byrd brought the brightness, Adams the grit. Together, they balanced light and shadow perfectly.

The title track, The Cat Walk, opens with a slow, swinging rhythm and that unmistakable Byrd-Adams dialogue — trumpet shining, baritone purring beneath. The theme is simple but unforgettable, a slow saunter through an imagined city street: stylish, unhurried, cinematic. Byrd’s solo is economical, full of short phrases and impeccable timing. He doesn’t push — he lets the rhythm do the work. Pearson’s piano, meanwhile, adds harmonic sophistication without ever crowding the frame. This is a record that understands restraint.

Say You’re Mine changes the mood — a ballad of disarming tenderness. Byrd’s tone softens to velvet, his lines slow and unguarded. Adams plays just behind him, a low hum of warmth. Philly Joe Jones, ever the dramatist, switches from sticks to brushes, adding texture rather than pulse. The piece breathes. You can almost feel the smoke in the room, the faint clink of glasses somewhere behind the horn lines.

Then comes Duke’s Mixture, a clever Pearson composition that plays with rhythm and key changes. The tune bounces between moods — from brisk swing to relaxed stroll — showcasing Byrd’s agility. His phrasing remains lyrical even when the tempo quickens. The chemistry between Byrd and Adams is extraordinary here: they weave rather than trade, their tones interlocking like facets of the same voice. It’s jazz as design — geometric, balanced, and full of purpose.

Each Time I Think of You brings things inward again. It’s a ballad of suspended emotion, Byrd at his most introspective. His trumpet almost whispers; Adams responds in kind, his baritone like a low consoling voice. Pearson plays with delicacy — chords like soft rain, perfectly timed. It’s not sentimental; it’s composed, poised, human.

Then Say You’re Mine (Alternate Take) offers a slightly rawer read, followed by Hello Bright Sunflower — a burst of brightness to close. The melody is cheerful, simple, optimistic. After the cool restraint of the earlier tracks, it feels like stepping out of shade into light. The phrasing is still meticulous, but the energy lifts. It’s the perfect ending — not grand, not loud, just warm.

In the listening bar, The Cat Walk plays like a slow exhale. It doesn’t demand attention; it earns it. The rhythm section keeps everything afloat — Jones’ cymbals crisp and dancing, Jackson’s bass clean and resonant. The soundstage is pure Van Gelder: trumpet forward but never harsh, piano gleaming, sax just off to the left like a voice in another room. On a fine system, the details glow — the breath through Byrd’s horn, the gentle drag of brush on snare. It’s tactile sound, beautifully weighted.

There’s something cinematic about the whole affair. It’s not a concept record, but it plays like one. Each track feels like a scene — the late-night walk, the passing glance, the quiet confession. Byrd was always elegant, but here he becomes architectural. You can sense his design sense in every choice — tone, phrasing, pacing. It’s the sound of a man who understands both silence and movement, and how one gives meaning to the other.

Culturally, The Cat Walk sits at an interesting hinge. 1961 was the twilight of classic hard bop — before Coltrane’s modal explorations and Ornette’s freedom fully changed the landscape. Byrd didn’t chase the avant-garde. He polished what he had until it gleamed. This record feels like a closing chapter — the last perfect form of a style before the ground shifted. But even as it honors tradition, you can sense his curiosity flickering beneath the polish. There’s air in his phrasing, looseness in the rhythm — the same instincts that would later carry him to Free Form and A New Perspective.

Play The Cat Walk in a room with low light and good company, and it becomes a kind of atmosphere rather than an album. The horn blend feels like breath in motion; the groove never breaks stride. It’s the kind of record that makes you aware of your own rhythm — how you lift a glass, how you listen, how you breathe.

That’s the secret here. The Cat Walk isn’t about display; it’s about feel. It’s not trying to impress; it’s trying to move gracefully through space. Donald Byrd understood that music, like life, doesn’t always have to sprint to make progress. Sometimes it’s enough to walk well — to move with balance, with taste, with quiet conviction.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.