The Velvet Underground & Nico – The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967)

By Rafi Mercer

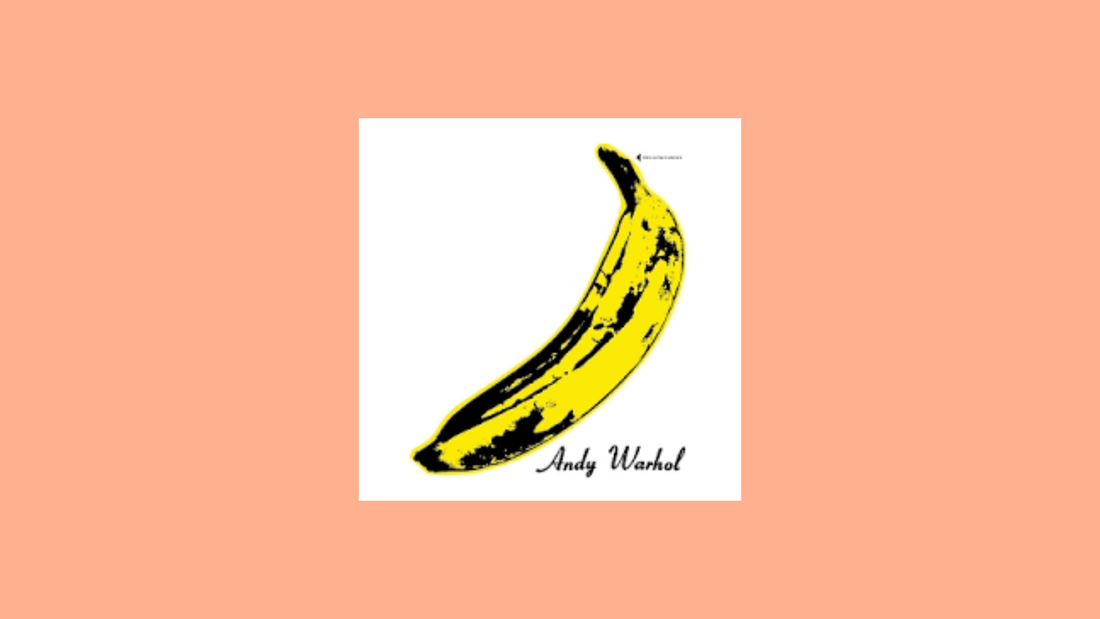

A tambourine rattles, Lou Reed’s guitar scratches out a steady rhythm, and John Cale’s droning viola begins to saw through the mix. Then comes that unmistakable voice: Nico, cool, distant, almost dispassionate. “Sunday morning, praise the dawning…” With its banana-sleeved cover by Andy Warhol and its uncompromising sound, The Velvet Underground & Nico, released in 1967, remains one of the most influential albums in modern music. More than a debut, it was a rupture — a record that turned noise into art, taboo into subject, and the underground into a creative blueprint.

The cultural backdrop is essential. While the Summer of Love was painting psychedelia in bright, utopian colours, The Velvet Underground painted in shadows. They sang about heroin, sadomasochism, urban alienation, and fragile beauty — subjects far removed from San Francisco sunshine. Based in New York, they absorbed the rawness of the city, the minimalism of downtown art, the detachment of Warhol’s Factory. Where most 1960s rock promised escape, the Velvets documented reality — stark, unsettling, yet undeniably poetic.

The album opens deceptively gently with “Sunday Morning,” a lullaby touched with paranoia, Reed’s fragile vocal offset by celesta sparkle. But from there, it plunges into darker terrain. “I’m Waiting for the Man” recounts a drug score in uptown Harlem, driven by Reed’s deadpan vocal and a relentless piano riff. “Venus in Furs,” with Nico’s icy delivery and Cale’s viola drone, dives into the world of S&M, its lyrics lifted from Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s novel. “Heroin,” perhaps the album’s centrepiece, is stark and harrowing: a two-chord vamp that alternates between calm drift and frenzied chaos, mirroring the rush and crash of the drug itself.

Elsewhere, “All Tomorrow’s Parties” showcases Nico’s voice at its most statuesque, her contralto turning Warhol’s Factory gatherings into gothic ritual. “Femme Fatale,” written for Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick, is almost pop but tinged with melancholy. “European Son,” the chaotic closer, explodes into noise, free-form and abrasive, as if tearing apart the conventions of rock entirely.

What makes the album extraordinary is its refusal of polish. Reed’s vocals are flat, almost conversational. Cale’s viola is abrasive, droning. The production is raw, sometimes murky. But that roughness is its strength. It feels lived-in, real, unvarnished. It is music that does not seduce but confronts. At a time when pop was becoming increasingly polished, The Velvet Underground insisted on imperfection, distortion, grit.

Initially, the record sold poorly. Mainstream audiences found it too abrasive, too strange. Yet its influence grew quietly but profoundly. Brian Eno famously remarked that while only a few thousand bought the album at first, “everyone who did formed a band.” Punk, post-punk, noise rock, alternative, indie — all carry its DNA. Its minimalism, its honesty, its embrace of taboo opened doors that remain open today.

Listening now, the album feels remarkably inclusive despite its harshness. It is not music of virtuosity or exclusion. It is direct, simple, democratic. Anyone with a guitar, a drum, a voice could imagine themselves making music like this. Its subject matter may be dark, but its ethos is liberating: art does not have to be pretty to matter, and beauty can be found in the raw and broken.

For women, Nico’s presence is crucial. In a scene often dominated by male posturing, her voice adds gravity and distance. She is not muse but participant, not accessory but co-creator. Her cool, androgynous delivery gave the album its otherworldly aura, balancing Reed’s streetwise realism. Together, they embodied a world where gender, sexuality, and identity could be fluid, unstable, adventurous.

On vinyl, the album retains its punch. The crackle only amplifies its grit, the drone of Cale’s viola vibrates through the speakers, the chaotic jams fill the room with menace and energy. The banana cover — designed by Warhol, complete with peelable sticker on the original pressing — has become one of the most iconic pieces of album art, symbolising both pop art wit and underground provocation.

Nearly sixty years on, The Velvet Underground & Nico still feels radical. Its themes remain raw, its sound still cuts through, its honesty remains bracing. It reminds us that music can confront as well as comfort, disturb as well as soothe. And that sometimes, the most influential works are those that dare to be difficult.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.