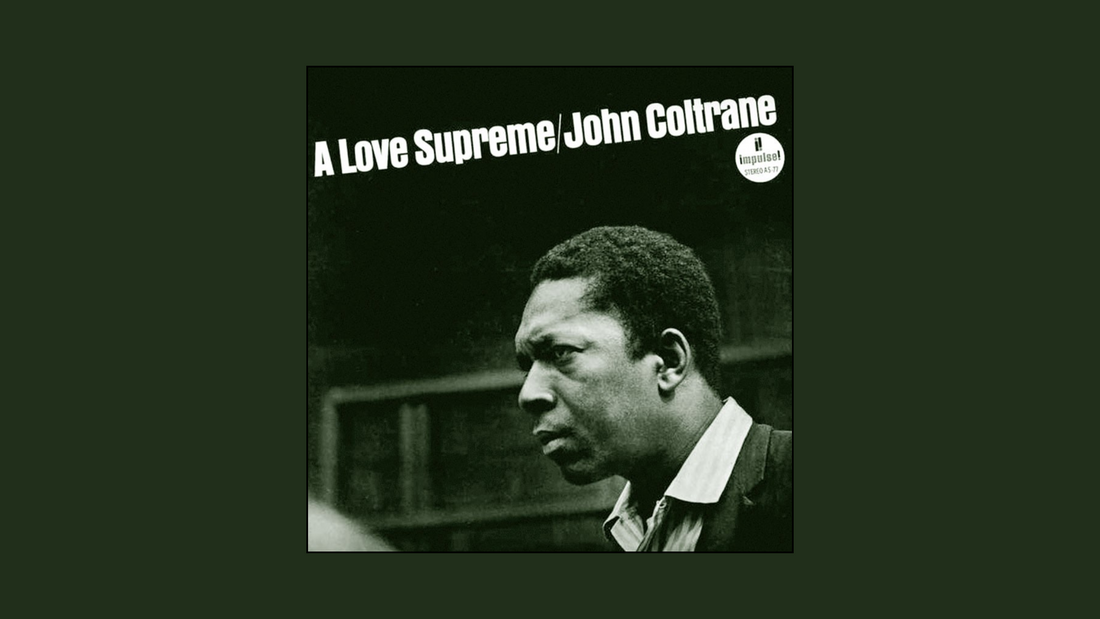

John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme (1965) — a spiritual jazz masterpiece recorded in one night

By Rafi Mercer

It begins with a gong, a shimmer of sound like the opening of a ritual, followed by Jimmy Garrison’s bass, steady and deliberate, outlining a four-note motif that will carry the entire work. Elvin Jones’s drums arrive with waves of cymbal, McCoy Tyner’s piano chords glow with understated insistence, and then Coltrane himself enters, the tenor saxophone declaring a theme that feels both simple and monumental. From this moment onward, A Love Supreme unfolds not as a conventional jazz album but as a declaration, a prayer pressed into vinyl, a work of devotion that has outlived its time and become a cornerstone of twentieth-century art.

By the end of 1964 Coltrane was no longer simply a jazz musician but a man who had channelled his private struggles into something larger. Only a few years earlier he had been adrift, consumed by heroin and alcohol, his career in jeopardy, his life in danger of collapse. In 1957 he experienced what he called a spiritual awakening, a moment that freed him from addiction and gave him a new sense of purpose. He immersed himself in spiritual texts across traditions, from Christianity to Hinduism, Islam to African mysticism, absorbing rather than choosing, finding in each a language of devotion. The notes he wrote in the A Love Supreme liner reflect this, a simple acknowledgement of gratitude to a higher power for his salvation. That spiritual clarity fed directly into his art, sharpening his sound, deepening his search, and giving rise to this suite.

The quartet assembled for the session — Tyner, Garrison, Jones, and Coltrane — had already forged a collective sound that was as powerful as it was intimate. Tyner’s voicings created a harmonic universe both lush and austere, Garrison’s bass lines were the heartbeat of the band, repetitive but resonant, Jones’s drumming was elemental, a tide in constant motion, and Coltrane’s saxophone was the vessel through which prayer was transformed into breath and tone. Together they achieved a sound that felt unbound by category, neither small group jazz nor big band, neither chamber music nor liturgy, but something encompassing all of these at once.

The suite opens with “Acknowledgement,” where Coltrane presents the four-note theme that becomes mantra. It is both anchor and invocation, a simple shape repeated and reinterpreted until it transcends itself. In the closing minutes, Coltrane even chants the words “a love supreme,” intoning them nineteen times, his voice fragile yet insistent, as though reminding himself of the devotion he wishes to carry. The music then turns to “Resolution,” which lifts the energy into something radiant, Coltrane’s horn urgent yet centred, Tyner’s piano cascades bright and percussive, the bass firm, the drums surging. What began as prayer becomes determination, a vow to live that devotion through action. The fire builds further in “Pursuance,” where Jones opens with a drum solo of volcanic energy, rhythms tumbling forward like a storm. Coltrane answers with improvisations that spiral upward, urgent and searching, Tyner and Garrison keeping pace with unrelenting drive. It is the sound of pursuit, of a soul straining for the divine. The final movement, “Psalm,” brings stillness: Coltrane plays freely, without set tempo, shaping each phrase to mirror the words of a poem he had written, essentially turning prose into melody. The effect is intimate and solemn, as if the saxophone itself were reciting prayer. The suite closes not with climax but with benediction, fading into silence.

When the album appeared in 1965, it was recognised instantly as something extraordinary. Critics and listeners alike sensed that this was no ordinary jazz record but a work of devotion with universal resonance. It sold remarkably well for a record of its kind, reaching beyond jazz audiences to touch listeners from every background. Over the decades, its reputation has only grown. Musicians across genres have drawn from it, from rock to classical to electronic. Spiritual communities of many kinds have adopted it as devotional music. For individuals, it has become a companion in grief, meditation, and joy. Its power lies in its sincerity: Coltrane did not posture or preach, he simply offered his gratitude through sound, and that honesty is what continues to move listeners.

To hear it on vinyl is to step into ceremony. The warmth of the pressing amplifies the intimacy of the quartet, every cymbal wash and bass resonance close at hand. The crackle of the needle blends with the opening gong, making the ritual tactile. The music does not overwhelm but surrounds, turning any room into a sanctuary. You need not understand jazz theory or share Coltrane’s faith to feel its weight. The four-note mantra is as clear as a heartbeat, the journey from invocation to benediction as natural as breath. It is music that welcomes rather than excludes, an open space where women and men, newcomers and connoisseurs alike can find themselves reflected in its devotion.

Nearly sixty years on, A Love Supreme has lost none of its gravity. It remains not only Coltrane’s masterpiece but one of the most profound recordings in modern history. It proves that music can be more than entertainment, more than performance, more than culture — it can be prayer, architecture for the soul, a structure through which presence and transcendence are made audible. Coltrane’s wish was simple, “to make others happy through music.” With A Love Supreme he went beyond happiness, offering instead a sense of wholeness, a reminder of what it means to give thanks in sound.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.