The Art of Ice: Why It Matters in a Whisky Glass

By Rafi Mercer

Most people think of ice as functional. Something you drop in a glass to cool a drink. But anyone who has spent time in a listening bar knows it is much more than that. Ice is part of the ritual, as essential as the whisky itself, as influential as the music in the room.

The Japanese figured this out long ago. In Tokyo’s whisky bars, ice is treated with reverence. Bartenders carve single spheres or perfect cubes by hand, not for show but for function. A sphere melts slower than shards. A dense cube chills without flooding the whisky. The clarity of the ice — how clouded or clean it looks — speaks to the water, the freezing process, the patience with which it was made. Drop one of those crystal-clear blocks into a glass, pour a measure over the top, and you can hear it sing — a soft crack as the liquid embraces the solid.

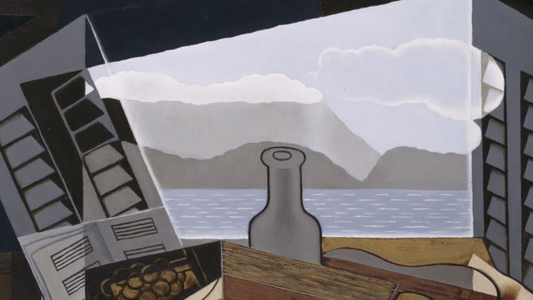

It’s the same philosophy as the listening bar: restraint, precision, attention to detail. A record played on horn speakers in a tuned room is not “just music,” it’s architecture. A cube of hand-cut ice in a glass is not “just cold,” it’s tempo. It sets the pace of the drink, dictates how long it will last, shapes how each sip evolves.

And it isn’t only about slowing melt. Ice changes flavour. Too much, too fast, and the whisky dilutes into something shapeless. The right cut, the right density, and you get balance: first the spirit at full strength, then slowly softened, opening new notes, revealing new layers. Like a track that builds and releases, the drink shifts over time.

I’ve always thought of ice as a kind of silence in the whisky ritual. On its own, it seems empty, transparent, nothing. But placed with care, it gives shape to what surrounds it. The way silence frames sound, ice frames whisky. Both are overlooked until you notice them. And once you notice, you can’t go back.

Of course, there’s debate. Purists will say whisky should never see ice at all. Others swear by a splash of water instead. And they’re not wrong. But in the context of a bar — especially a listening bar — the ice becomes part of the theatre. The sound of the block against glass, the shimmer as it catches the low light, the slow crackle as temperature shifts. It’s sensory, atmospheric. It belongs to the moment.

This is why you’ll often see bars invest in ice machines that produce dense, flawless blocks, or train staff to carve spheres by hand. It’s not about gimmick. It’s about respect. Respect for the drink, for the customer, for the ritual. The same respect that makes a bar spin records on vinyl instead of queuing a playlist.

So next time you pour a whisky at home, think about the ice. Don’t just grab cloudy cubes from the freezer tray. Try making larger blocks. Experiment with boiled water for clarity, or invest in moulds that give you spheres. Notice how the shape changes the pace of the drink, how the melt alters the flavour, how the ritual changes your attention. You may find, as I have, that the ice is not background at all.

Because in the end, ice is like listening. Done carelessly, it’s forgettable. Done with intent, it becomes part of the experience. It slows you down, grounds you, opens new details. It reminds you that even the smallest things — a cube in a glass, a silence in a song — can transform the way we experience the world.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe here, or click here to read more.