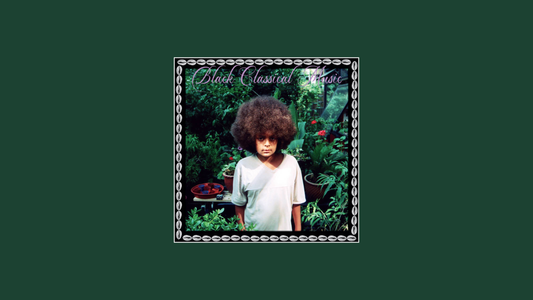

Black Classical Music – Yussef Dayes (2023)

Yussef Dayes’ Black Classical Music (2023) bridges heritage and horizon — rhythm as reflection, groove as grace.

By Rafi Mercer

There’s a moment, every few years, when you can feel a tradition flicker back into life — not as nostalgia, but as force. Black Classical Music, Yussef Dayes’ debut solo album from 2023, is one of those moments. It’s not about revival; it’s about return.

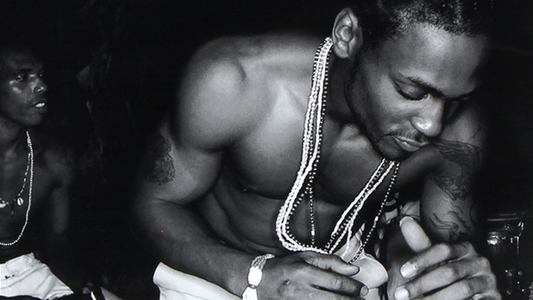

I first heard it in a small space in Soho — a record shop turned listening room for the evening. The sound was immaculate: brushed cymbals curling around sub-bass, chords moving like water through light. Dayes sat behind the kit on the playback video, smiling — that half grin of someone who’s learned to make time elastic.

This is not a jazz record in the old sense, nor is it an electronic record. It’s a hybrid of muscle and meditation. The drumming is physical but fluid, alive with the intuition of someone who’s absorbed rhythm into reflex. Every snare snap feels like a punctuation mark; every brush stroke, a breath.

The title track begins like invocation — Dayes’ kit rolling beneath shimmering chords and Kamasi Washington’s tenor sax. There’s warmth, but also weight. The groove expands, opens, then folds again. You can hear the lineage: Miles Davis, Fela Kuti, Herbie Hancock — not copied, but reinterpreted. Dayes has built a bridge between soul, spiritual jazz, and modern beat culture, and he walks across it like it’s home.

What’s most striking is how Black Classical Music balances energy and elegance. It could easily have been indulgent — a showcase for technique — but it never is. Every track has purpose. “Afro Cubanism” swings with precision; “Marching Band,” featuring Masego, fuses gospel, funk, and loose London heat. Then comes “Chasing the Drum” — six minutes of rolling meditation, Dayes locked in with bass and Rhodes in perfect communion.

Listening closely, you can sense how he treats rhythm as architecture. The cymbals define the room; the kick shapes its depth. Through a good system, the album sounds almost three-dimensional — the space between instruments rendered like light through smoke. It’s not production for spectacle; it’s production for feeling.

There’s something spiritual in his restraint. Dayes knows when to leave space — that essential jazz instinct that silence can groove harder than sound. You hear it on “Rust,” where slow harmonies float over distant percussion, and again on “Tioga Pass,” a track that feels like sunrise over fog. It’s not performance; it’s presence.

Dayes has always understood the tension between groove and grace. His earlier work with Yussef Kamaal introduced that elastic sense of swing — where drums lead harmony, not the other way around. Black Classical Music takes that instinct further, crafting entire worlds out of pulse. The album feels lived in, not layered; you can hear musicians responding to one another, not to software.

There’s also a deep humility in how he frames the music. The title could have been provocative, but it isn’t. It’s reclamation — an assertion that black expression is classical, that these rhythms are history, not departure. Dayes doesn’t intellectualise it; he just plays it, with generosity and conviction.

Halfway through the album, “Crystal Palace Park” changes the temperature. Rhodes chords shimmer like reflections on wet pavement, bass murmurs low, and the drums roll like conversation — never soloing, always speaking. It’s London and Los Angeles, Lagos and Kingston, all folded into one listening moment.

Later, “Pon di Plaza” and “The Light” stretch further outward — modern jazz crossing into electronic atmosphere, without losing breath. There’s a looseness here that feels earned: Dayes in full control, but never rigid. His drumming becomes melody, not rhythm — phrases and shapes, not just beats.

What ties everything together is tone. The record sounds warm, analogue, handmade — rich in imperfection. You can hear the wood of the kit, the hiss of the tape, the slight detuning that gives everything texture. It’s that attention to detail — the reverence for human feel — that makes it a listening album in the purest sense.

Played through speakers in a quiet room, Black Classical Music fills space like a living organism. The bass moves gently underfoot, the cymbals shimmer at the edge of hearing. It’s not background; it’s atmosphere. You can work to it, think to it, move to it — but you’ll always end up listening.

And that’s what makes it special. This isn’t music demanding applause; it’s music that trusts awareness. Dayes’ playing feels like meditation through motion — repetition as reflection. Each stroke of the snare feels like a breath returning home.

Toward the end, “Woman’s Touch” with Leon Thomas brings tenderness — voice and rhythm finding common language. The track closes with a fade that feels almost ceremonial, as if Dayes is bowing to the record itself. You realise then that Black Classical Music isn’t just about jazz; it’s about balance — of heritage and innovation, of speed and stillness, of body and thought.

Listening now, I’m reminded how rare this kind of confidence is — to play without forcing, to let rhythm speak for itself. Dayes doesn’t chase the beat; he listens to it. That’s his genius. He knows that drumming isn’t about control; it’s about connection.

In the end, the title lands perfectly. This is Black Classical Music — not a genre, but a gesture: to honour what came before while building what comes next. It’s the sound of continuity.

And in a world that forgets too quickly, Yussef Dayes has given us something that remembers.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters.

For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.