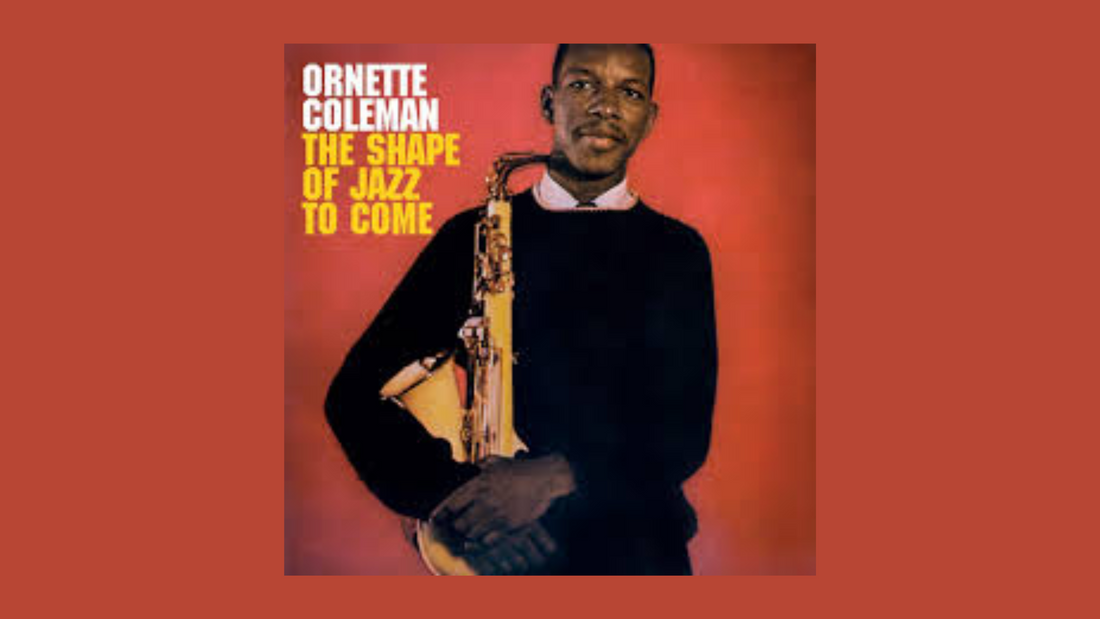

Ornette Coleman – The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959)

By Rafi Mercer

The first sound you hear is not polite. It is not slick, not rounded, not dressed up for approval. It is Ornette Coleman’s alto saxophone, thin and piercing, a voice that feels more like speech than song, tremulous and insistent, carrying a weight of sorrow and defiance. “Lonely Woman” begins, and suddenly you are no longer listening to a conventional jazz record, but to a declaration, a kind of manifesto written in air. There is no piano laying out chords beneath the melody. Instead, Charlie Haden’s bass moves with dark gravity, Billy Higgins’s cymbals shimmer and surge, and Don Cherry’s pocket trumpet wails in sympathetic counterpoint. The effect is startling: a lament that moves forward, restless, uncontained.

In that moment, The Shape of Jazz to Come reveals itself as a fracture point, a record that refuses to be background. It demands attention. It unsettles, confounds, but also mesmerises. In the long gallery of 1959, a year that gave us Kind of Blue, Mingus Ah Um, and Giant Steps, Ornette’s album occupies a stranger position. It is less polished, less easily absorbed, yet perhaps the most radical. Where Davis and Coltrane expanded jazz’s language, Ornette proposed that the language itself could be broken open, spoken without grammar, improvised in real time.

Coleman was, by every measure, an outsider. Raised in Fort Worth, largely self-taught, he endured the disdain of musicians who called his tone wrong, his phrasing clumsy. He carried a plastic saxophone when others carried gleaming brass, not as a gimmick but because it was what he could afford. In Los Angeles he scraped by, gigging in dives, surviving on sheer stubbornness. Yet in 1959, he convinced Atlantic Records to take a chance, and what they captured in the studio was nothing short of incendiary.

The title itself, The Shape of Jazz to Come, is both prophecy and provocation. It suggests that this music is not a sideline, not an eccentric diversion, but a vision of the future. It was a claim that unnerved his contemporaries. To many, it sounded like chaos. Miles Davis dismissed it outright. Roy Eldridge called it “bunk.” Audiences walked out. And yet, others — John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet, Leonard Bernstein, eventually Coltrane himself — recognised something profound. They heard freedom, honesty, a stripping away of artifice.

Listen to “Lonely Woman” on vinyl, and the effect is even sharper. The horns’ unison line feels ragged and human, not machine-perfect, and that imperfection is its truth. Haden’s bass is dark, almost mournful, anchoring a music that otherwise seems to float untethered. Higgins’s drumming is restless but never overbearing, cymbals whispering like waves. What emerges is less a song than a mood, a state of being: grief that will not settle, grief that must move.

The following track, “Eventually,” bursts with energy, its theme skipping forward with bright insistence. Here, Coleman’s alto darts unpredictably, lines that ignore traditional harmonic landmarks, careening instead toward melodic instinct. Don Cherry answers with his own brash, playful voice, sometimes colliding, sometimes echoing. It is not orderly, but it is alive. “Peace” comes next, and the title is no accident. The horns sing a theme of tenderness, and though the improvisations still wander, they never lose their lyricism. It feels like a hymn — fragile, searching, and deeply sincere.

“Focus on Sanity” crystallises Coleman’s philosophy. The theme leaps out boldly, then dissolves into improvisation where each instrument speaks as an equal. Haden’s bass does not merely walk; it converses. Higgins is not timekeeper but co-conspirator. The horns weave in and out, sometimes aligned, sometimes apart. The effect is of a living organism, constantly changing, always responsive. “Chronology” closes the record on a lighter note, almost cheeky, its quick-stepping theme suggesting that freedom is not only solemn but joyous.

What is striking now, more than sixty years on, is how coherent it all sounds. The accusations of chaos no longer hold. You hear instead the quartet’s extraordinary attunement. Coleman and Cherry move like two sides of a single thought, one voice piercing, the other rounded. Haden listens with rare sensitivity, choosing notes that anchor but do not dictate. Higgins drives the music forward with swing that is loose, open, propulsive. Far from disorder, this is deep conversation, one that flows with intensity and empathy.

Coleman called his concept harmolodics — a democracy of melody, harmony, and rhythm, where no single element dominates. The word itself is slippery, never fully defined, but the practice is clear on this record. The music breathes as a collective. There is no hierarchy, no chord changes demanding obedience. Instead, there is trust: trust that each musician can speak and still be heard, that the music can make sense without a map.

To some ears, that openness remains unsettling. Jazz had always been about improvisation, yes, but within agreed frameworks. Standards, blues forms, chord progressions were the shared language. Coleman suggested that language itself could be remade each time. It was not destruction, but liberation. And that, perhaps, is why The Shape of Jazz to Come retains its power. It is not polished product but raw proposition: what if music could be free?

Hearing it in a listening bar today is a vivid experience. The record does not sit politely in the background; it reshapes the air. “Lonely Woman” drapes the room in its mournful gravity. Conversations pause, attention leans forward. Some listeners are transfixed, others unsettled. That split response is part of the music’s life. It provokes, it asks something of you. In a world saturated with sound designed to soothe, Coleman’s record insists on honesty, however uncomfortable.

Yet there is beauty here, unmistakable. Coleman’s tone, though often described as “nasal” or “piercing,” carries an intimacy that polished saxophonists rarely achieve. It feels unvarnished, human, like speech faltering in the throat. Don Cherry’s trumpet, with its cracked brightness, adds another shade of vulnerability. Together, their sound is closer to folk song than to high art — direct, imperfect, deeply communicative.

Legacy, too, is unavoidable. This record set the stage for free jazz, for Coltrane’s later explorations, for Albert Ayler’s wails, for Cecil Taylor’s abstractions. It opened doors that could not be closed. Even those who dismissed it could not ignore it. It expanded the horizon of what jazz could be, not by offering a perfected model but by insisting that imperfection, exploration, and risk were legitimate. It made jazz less about correctness, more about courage.

On vinyl, the record is a tactile experience. The Atlantic pressing has warmth that draws you in, a physicality that streaming cannot replicate. The horns leap forward, the bass hums with body, the drums shimmer with room tone. The imperfections — tape hiss, mic bleed — only enhance its presence. It feels alive, urgent, now.

Coleman himself would go on to further extremes: Free Jazz in 1960, a double quartet improvising simultaneously, then symphonic works, electric bands, harmolodic funk. But The Shape of Jazz to Come remains his most concentrated statement, the moment when the door first opened. It still sounds radical not because of volume or density, but because of honesty. It dares to sound exactly like itself, nothing more, nothing less.

To listen deeply is to accept its invitation: to let go of expectations, to hear without the safety net of chords, to follow the melody wherever it leads. It is a reminder that listening is not passive but active, an act of trust. And in that sense, the shape of jazz to come was always the shape of listening itself.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.