Nagra — Swiss Miniature, Global Authority

By Rafi Mercer

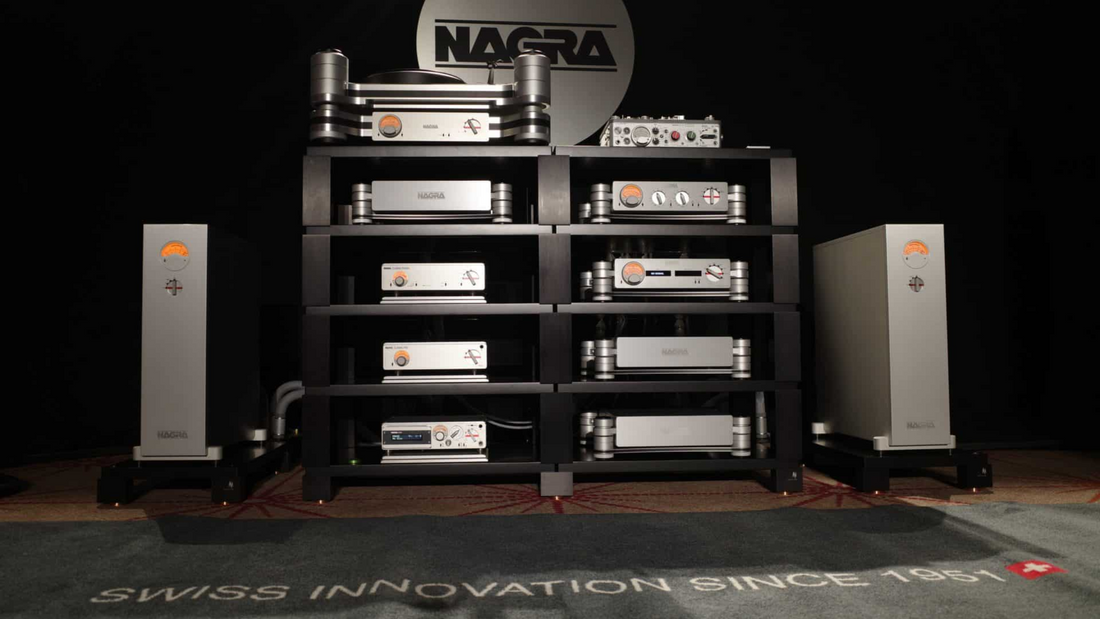

Some equipment wears its weight in chrome and glass. Others prove their authority by doing more with less. Nagra belongs to the latter. Compact, jewel-like, impossibly precise, these Swiss machines were born not in audiophile salons but in the field — slung across the shoulders of journalists, sound engineers, and filmmakers. To this day, their presence in a listening bar carries the same message: fidelity is not about size, but about trust.

Nagra’s story begins in 1951, when Polish émigré Stefan Kudelski, working in Lausanne, built a portable tape recorder that could fit in one hand. He called it the Nagra I, from the Polish word “to record.” It was small, battery-powered, and astonishingly accurate. Very quickly, the world noticed. Radio reporters adopted it, film crews relied on it, and by the 1960s the Nagra III was standard kit on movie sets from Paris to Hollywood. Entire generations of soundtracks — Godard’s experiments, Scorsese’s street scenes — were captured through Nagra reels.

That broadcast and cinematic DNA is what makes their transition into hi-fi so compelling. When Nagra turned to amplifiers, preamps, and phono stages, they carried the same aesthetic: compact aluminium cases, precise meters, switches that felt like instruments rather than consumer controls. In a listening bar, to see a Nagra preamp on a counter is to glimpse a piece of broadcast history repurposed for atmosphere.

The sound, too, reflects that heritage. Neutral, fast, and uncoloured, Nagra electronics are less about warmth or power than about truth. They let the music through without adornment, the way a sound engineer would want it captured. I once heard a Nagra Classic Amp driving Living Voice speakers in a small London venue. The record was Alice Coltrane’s Journey in Satchidananda. The harp lines floated, the bass notes pulsed like currents of air, the room itself seemed suspended. Nobody spoke. The machine wasn’t drawing attention to itself, but to the space the music created.

This is the paradox of Nagra: it is both miniature and monumental. Small enough to fit on a crowded bar counter, yet commanding enough to anchor the sound of an entire night. Its aesthetic is almost medical — brushed aluminium, clear meters, surgical precision — but in the right context it becomes intimate. Patrons who may never have seen one before lean closer, intrigued by its scale, reassured by its steadiness.

In comparison to McIntosh’s blue-lit theatre or Audio Research’s glowing tubes, Nagra feels almost ascetic. But in bars that prize focus — where silence between notes is as important as the notes themselves — Nagra’s restraint becomes its magic. It proves that fidelity is not about spectacle, but about clarity.

Seventy years after Kudelski built the first recorder, Nagra remains family-owned, still crafting in Switzerland, still obsessed with detail. Their machines are timeless not because they are nostalgic, but because they never stopped being useful. In a world where most technology is disposable, that continuity itself is authority.

In a listening bar, Nagra reminds us that the room doesn’t need to be filled with power to be filled with presence. That the smallest box can hold the deepest silence. That sound, when rendered with clarity, can stop a room more effectively than spectacle.

Rafi Mercer writes about the spaces where music matters. For more stories from Tracks & Tales, subscribe, or click here to read more.